African matters, in this case its art, is a fraught wager, given the burden of history, immoral expediency, fetishism, and a greater range of prejudicial and projected perceptions as to what Africa, a benighted continent, might mean for the world. Here, I must show my hand, and return to Steve Bantu Biko’s prophecy, that Africa would give the world its ‘human face’. Beyond power, geopolitical shifts, North/South conflicts, etc., it is this promise to which I hold fast.

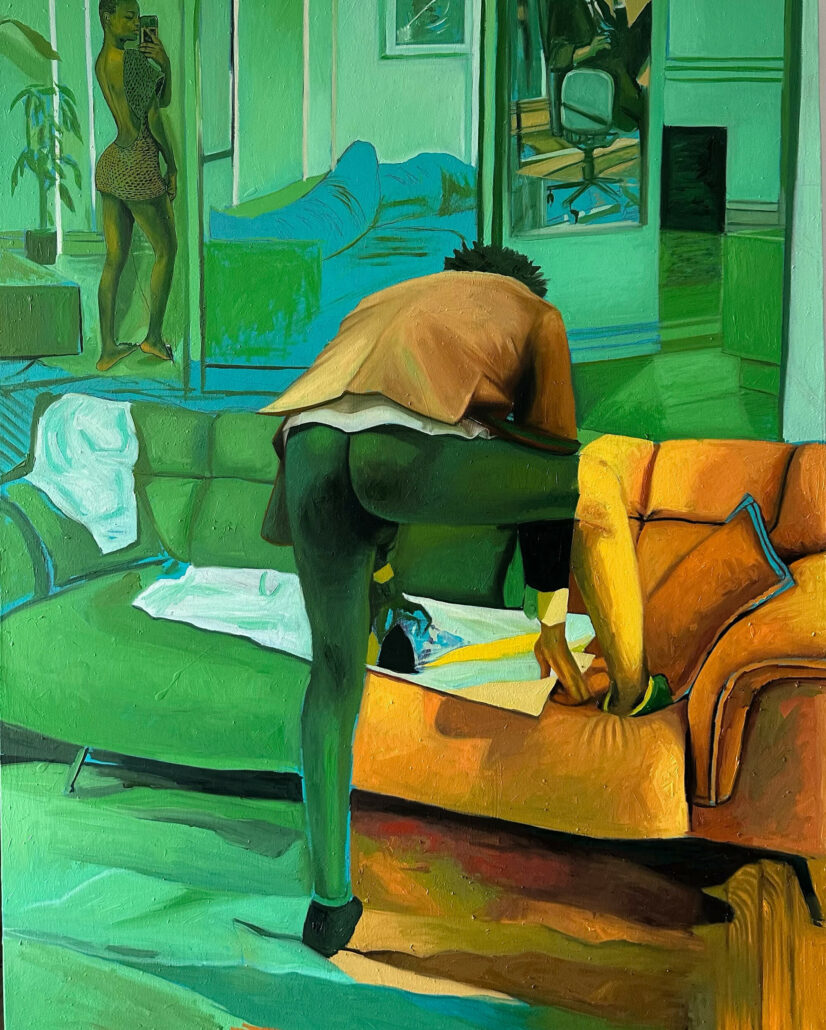

Ayogu Kingsley, Saturday Morning, 2023. Oil on Canvas, 107 x 138 cm. Courtesy of Eclectica Contemporary.

As Precious Adesina of Artnet News noted, a ‘wider appreciation for contemporary African art and art of the African diaspora has grown dramatically over the last decade’ Similarly, the ‘Elevation of the Everyday’, the normalcy of African self-representation, which confounded the on-going perception of Africa as a zone of damage and beggary – in extremis. Referring to El Anatsui’s magisterial show at the Tate Modern, Adesina spoke of a wider interest, amongst African artists, in the use of everyday items and depicting scenes of the everyday. Indeed, Arte Povera, the most important European art movement in the second half of the 20th century, had found its perfect mirror in Africa, a continent more inspired than any other in the innovative repurposing of Western-metropolitan waste. Pointing to the nexus of colonial and post-colonial exchange, Adesina reminded us of the politics of a new African abstraction, built on repurposed waste, and the complex history of bondage upon which the excesses of Capital are founded.

In this regard, the new dawn in African art could be understood as a symptom of a radical revisionism, one in which the black body is no longer centre-stage, except as a body abstracted and deterritorialized, allowed to morph beyond its identitarian constraints. Not only do these emergent African artists resist co-optation, say by the ‘conventional, snooty art world’, they are operating excessively – in excess of the constrained shackles conventionally placed upon them. Does this mean that we are witnessing a new expressive freedom, one in which art is nudged from its pedestal, reintegrated into a more capacious design-world, a world in which value is radically relativized, in which new forces emerge?

‘In compelling artists to assimilate and integrate, we are in danger of killing the voice of a new generation’. For me, it is the last point that matters most – intricate complexity – for this, as I understand it, allows not only for a demystification of tradition, not least that of Black Portraiture, little more than a mannerism these days, a Stylization of Self, even a Redacted Self, in so as far Black Portraiture has now become saturated and null. I say this, notwithstanding the genius that remains within it, in the matter, say, of Amoako Boafo. Let’s forge ahead, ‘against cultural colonialism’, against regressive integration. ‘Let us reshape the discourse surrounding African art. Why should we consistently feel like the outliers, akin to unicorns?’ indeed. Though, for my part, I cannot imagine a better rejoinder to conformity and subjection, than to be perceived as a glorious equestrian anomaly. One of the curious strengths of the unicorn is a ‘power to render poisoned water potable’. Precisely.

This April, Eclectica Contemporary is excited to present ‘The Non-Art Crowd” featuring artists from different corners on the Continent of Africa, pushing the boundaries within their own painting practice and playing with painting and the everyday experience. Featuring Ayogu Kingsley, Adegboyega Adesina, Callan Grecia, Didier Viodé, Shaquille-Aaron Keith and Thebe Phetogo.

The exhibition will be on view from the 4th of April until the 11th of May, 2024. For more information, please visit Eclectica Contemporary.

Text by Ashraf Jamal.