In Kinshasa in the 60s, the arts were the preserve of students trained at the Académie des Beaux-Arts. From the 70s onwards, critics discovered a particular genre of painting that the ‘Art Partout’ exhibition revealed to the general public.

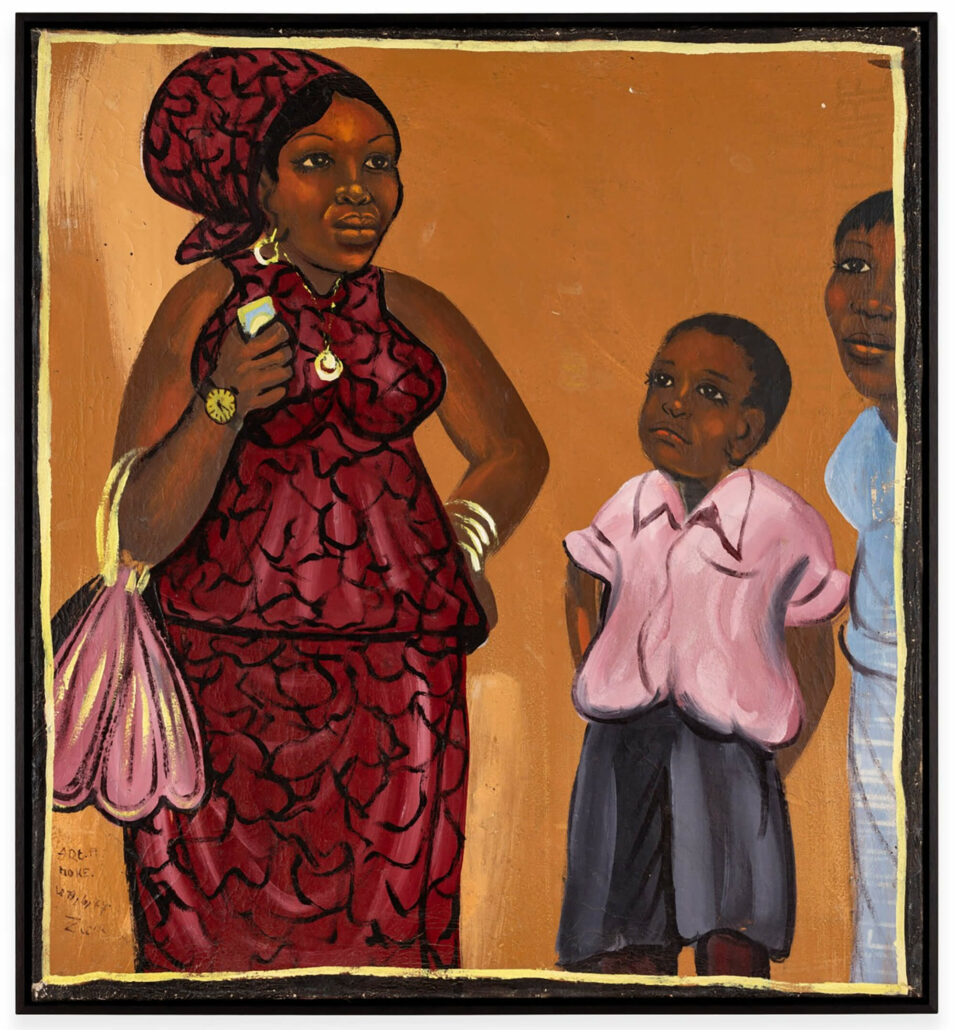

Moke, Untitled, 1977. Oil on flour sack from the matadi flour mill, 96 x 88.5cm. Photo © Studio Louis Delbaere, Courtesy Galerie MAGNIN-A, Paris

These were young artists concerned with the environment and the community who claimed to be Popular Artists. They produce a new form of figurative painting, depicting everyday life and drawing inspiration from political, economic and social events, which the entire population can identify. Chéri Samba, Ange Kumbi, Bodo, Chéri Chérin and Moke are the leading figures. For Jean-François Bizot, “Moke was Chéri Samba’s realist counterpart, specializing in street scenes, petty thieves, nightclubs and dancing. He died too soon, at the turn of the century.”

Mosengo Kejwamfi, alias Moke, was born in 1950 in the small village of Ibe, in the Bandundu province east of Kinshasa. In 1960, aged just 10, he arrived in Kinshasa at the time of independence.

There, he discovered the city’s energy and modernity, the sapeurs, the nightlife, the Rumba…, and the effervescence. Putting into practice Article 154, improvisation as a means of survival, he took up residence in the markets, collected the bottoms of industrial paint cans and began finger-painting on cardboard. He produced his first ‘popular’ painting in 1965 for the Independence Day celebrations: a depiction of General Mobutu waving to the crowd at the head of the parade on Boulevard du 30 juin.

He became the leader of the first generation of popular painters in Kinshasa. Moke set up his studio at the crossroads of Kasa-Wubu and Bolobo, in the heart of the fiery, rebellious capital he would never leave. Freed from state pressure, popular painting quickly became a privileged means of social communication. His depictions of seemingly banal everyday scenes reveal, against a backdrop of widespread poverty, the reality of living conditions far different from government promises.

In 1972, Moke met Pierre Haffner, who had just taken over as director of film activities at the Centre Culturel Français in Kinshasa. Haffner became Moke’s main sponsor until 1979 but didn’t stop there. Haffner showed him films and cartoons such as The Jungle Book, in which animals in the bush speak like humans, and painters at work, such as Picasso in front of Clouzot’s camera. He supplies him with pigments and canvas flour bags from the Matadi flour mill to express himself in larger formats.

Moke usually signs Artiste Peintre Moke to express his pride in being a painter. Except Chéri Samba, no other popular painter in Kinshasa has enjoyed a comparable career or achieved such public support as some Congolese music stars. Moke, a painter and reporter of

urbanity, presents current events in his canvases, thus fixing the collective memory.

The ‘Moke, Peintre’ exhibition focuses on his historic works from the 1970s and 1980s, in which he already excelled in the treatment of light, capturing the atmosphere and energy of Kinshasa with a minimum of means. In his scenes of interiors, couples, markets, and Nganda, the whole story is there, with no further chatter.

Pierre Haffner’s departure in 1979 was an upheaval for Moke, who lost his patron and interlocutor. For a time, he gave up painting to devote himself to working with clay, but fortunately, others were already turning their attention to his work. In the 1980s, his commissions multiplied, and Moke transferred the themes cultivated in the previous decade to larger formats and produced them with better acrylics.

On the 26th of September, 2001, Moke drank a Skol in his studio with Chéri Samba. No one suspected it would be his last. Shortly after his friend’s departure, he was struck down by cardiac arrest, brush in hand. Kinshasa had lost one of its most generous and talented figures.

The exhibition will be on view from March 28th until May 18th, 2024. For more information, please visit MAGNIN-A.

Written by André Magnin and Frédéric Haffner.