‘Kahlo, Sher-Gil, Stern: Modernist Identities in the Global South’ concludes the third exhibition by JCAF (Joburg Contemporary Art Foundation) on their first research theme – Female Identities in the Global South.

Installation view of exhibition entrance. Photographer: Graham De Lacy. Images courtesy of JCAF.

The exhibition presents the works of three pioneering women artists, Frida Kahlo (1907–1954), Amrita Sher-Gil (1913–1941) and Irma Stern (1894–1966), and JCAF is the first institution to present these iconic artists together in Africa.

The exhibition has three parts that examine the constructs of ‘cosmopolitan’ and ‘indigenous’ identities through portraiture and self-portraiture and brings together 1 work of each artist painted within 11 years of each other. It considers the time and place during which each artist produced their work and gives insights into their experiences, inspiration and concerns.

Installation view of Part 1 Historical Background. Photographer: Graham De Lacy. Image courtesy of JCAF.

The introductory section of the show presents black & white wallpapers showing the historical background, presenting a context of the era at the time – one for India, Mexico City and Congo.

Installation view of Part 2 Identity Formation, Amrita Sher-Gil. Photographer: Graham De Lacy. Image courtesy of JCAF.

Installation view of Part 2 Identity Formation, Irma Stern. Photographer: Graham De Lacy. Image courtesy of JCAF.

Installation view of Part 2 Identity Formation, Frida Kahlo. Photographer: Graham De Lacy. Image courtesy of JCAF.

The second is the archive area, an island archipelago per station for the artists. Each artist kept journals narrating their observations. There is film footage of the artists, with only one existing film on Kahlo in colour, one on Sher-Gil, short and monochrome, colour and then in sepia, and black & white film footage of Stern. The series of photographs of each artist maps their childhood to later in life, drawing together their synergies and discontinuities. These discontinuities started with a European-Modernist idea of art, life and worldview. Then, discovering local indigenous knowledge and context, the concepts that transformed their practice into the mature work that embodies the local identity – Mexicayotl, Indian Modernism and Conga. For all of them, there are these interesting parallels. Objects collected by the artists influenced their practice and are part of their cultural milieu. Kahlo collected over 400 artesanías (little Mexican folk paintings), pre-columbian objects and colour photographs. Sher-Gil collected miniatures and sculptural effigies during her stay in India and Stern, the world-famous Buli Stool, and other things linked to the Watussi tribe of Congo.

Installation view of the three rooms in Part 3 Portraits and Self Portraits. Photographer: Graham De Lacy. Image courtesy of JCAF.

In section three, the exhibition design references each artist’s cultural and architectural heritage, each work housed in a unique, individualised space – for Kahlo, the Pre-Columbian architecture of Mexico; for Sher-Gil, Sikh and Mughal architecture in India; and Stern, Watusi Congo vernacular architecture. A form is abstracted from the architecture to produce a motif that contextually represents the artist and the colour of the walls specific within that context – for Kahlo, a blue house, Red for Sher-Gil and golden yellow for Stern. There is a 5-year period between the paintings, during which the artists were all alive for 11 years.

Frida Kahlo

Frida Kahlo was born in 1907 – the Mexican Revolution was in 1910. This was a whole rebirth of Mexican society at the time – part of this show: the reflection of national and hybrid identities.

On the one hand, we know everything about Kahlo, but at the same time, very little. She referred to this as ‘the mask’, a Spanish term for a great concealer. Her life was marked by triumphs and tragedies, and her experiences profoundly influenced her art. She suffered from a childhood illness of Polio and severe spinal injuries sustained in a bus accident when she was 18 and underwent 34 surgeries and medical treatments. Kahlo increasingly transformed herself, embracing a complete Mexican identity and adopting the flamboyant clothing and hairstyle worn by the Zapotec women on the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.

In 1929, Kahlo married Mexican muralist Diego Rivera. Both were politically active and supported left-wing causes. Their relationship was tumultuous, with both partners having numerous extramarital affairs; they remained married until Kahlo died in 1954. She visited the United States, France, Spain, and Germany and was influenced by European art movements such as Surrealism. Despite her travels, Kahlo always considered Mexico her home and drew inspiration from Mexican culture and traditions in her art. Her paintings were highly personal and introspective; she painted 55 self-portraits. Kahlo developed a unique style that combined elements of traditional Mexican folk art, pre-Columbian art, and European Renaissance painting. She incorporated elements of magical realism, creating dreamlike and fantastical scenes in bold, bright colours and strong, defined outlines. Her work included symbolic imagery, such as animals, plants, and everyday objects, to convey deeper meanings. Kahlo painted 55 self-portraits throughout her career, saying, “I paint myself because I am what I know best.”

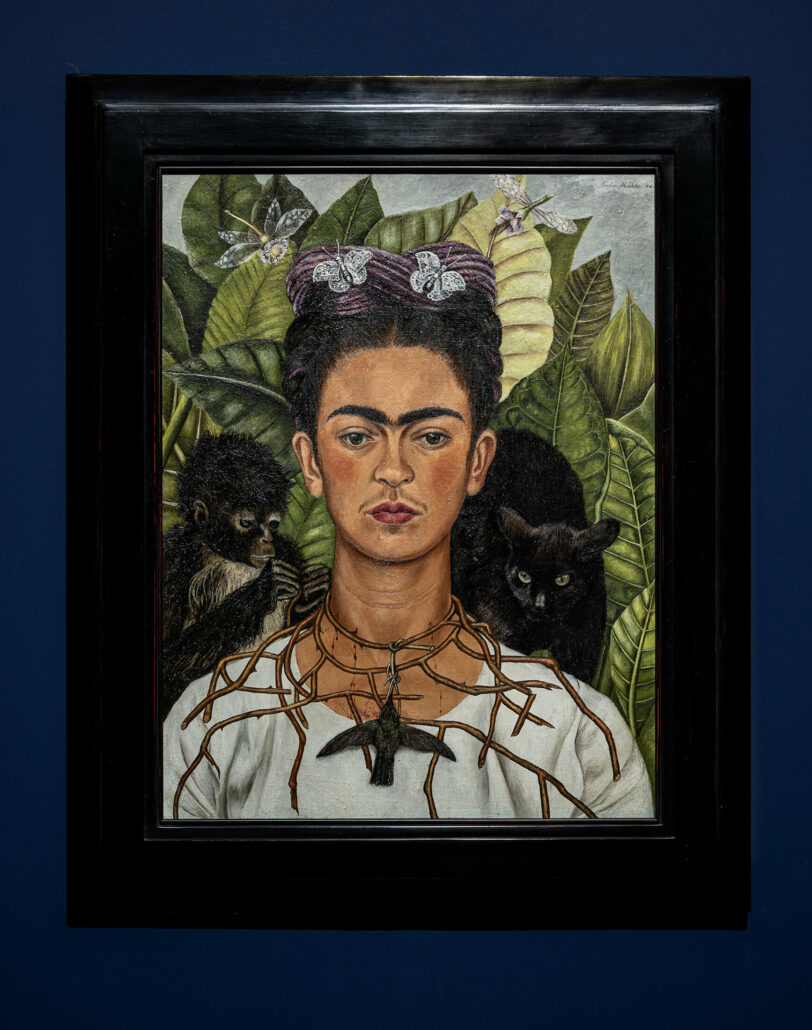

Frida Kahlo, Self Portrait with Hummingbird and Thorn Necklace, 1940. Oil on canvas pasted on board. Collection of the Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin, Nickolas Muray Collection of Modern Mexican Art. © 2022 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Image courtesy of JCAF.

The work exhibited is titled ‘Self-Portrait with Hummingbird and Thorn Necklace’ (1940). Kahlo includes her pet monkey, Fulang-Chang, and a cat. The hummingbird symbolises hope in pre-Colombian society; the formal shape of the bird mimics the form of her eyebrows. The butterflies are hair adornments, unable to fly; the dragonflies are flowers. The work is surreally filled with fantastical elements. Kahlo’s complex identity is foregrounded and shown to be a hybrid repository of the modern and natural worlds, religious and secular. The top of the work depicts the heavens, the middle the earth and the bottom death and the underworld. Khalo herself gazes out from the painting directly at (almost through) the viewer, her eyes vacuous – ‘the mask’. Feminists have claimed this gaze and said that for a woman to be emancipated, the gaze needs to be direct.

Amrita Sher-Gil

Amrita Sher-Gil was also of a mixed identity heritage. Born in Hungary to a Hungarian Jewish Mother and a father of Indian Nobility in 1913, she grew up in Hungary, went to India as a child, and then returned to Hungary. After studying in Paris, she moved back to India in 1934. A powerful, strong, complex, enigmatic woman, emancipated and educated, Sher-Gil was well-travelled and knowledgable. A rule breaker in all the right ways, she brought Modernism into India. Her painting style was influenced by both Western and Eastern art traditions, resulting in a unique style that combined elements of post-Impressionism and Indian classical art. She said about her work, “Picasso belongs to Europe. India belongs to me.”

Her work often featured a flattened perspective, simplified forms, and a sense of emotional intensity and psychological depth. Sher-Gil’s use of bright, vivid colours and expressive brushstrokes was not traditionally associated with Indian art.

Amrita Sher-Gil, Three Girls, 1935. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi. Image courtesy of JCAF.

At her grandparents’ house in India, she painted the work exhibited entitled ‘Three Girls’, 1935. They were her nieces; she knew them but chose not to use their names – like Stern – she simply calls them three girls. It is an extraordinarily subtle and remarkable painting; there is almost an isolation and solitude. The girls look down; there is no gaze, and they are in active submission, which is very much part of Indian society. This is another way to rethink feminism in the Global South; it would not be appropriate for young women in India to stare out of the frame at the White Colonial male. There is something quite profound about the fact that Sher-Gil, an independent, autonomous, educated woman, paints her cousins and nieces in this way, reinforcing this idea of the cultural identity of Indian women. She died at the age of 28, a prolific artist during which period she painted 50 self-portraits.

Irma Stern

Irma Stern’s parents were German Jews. She grew up on a farm in South Africa, and as a young child, she went blind for a short period. Burned into her memory was this idea of the landscape, environment and the vivid colours in the fields. As a child, Stern’s father was imprisoned by the British during the Anglo-Boer War, and the family left for Germany for a period and then returned to South Africa. Later, she returned to Europe to study art, spending time in Germany, France, and Italy. She was deeply influenced by the German Expressionist movement and the work of the Fauves and other modernist artists. Stern returned to South Africa in 1920 and began to establish herself as a painter. She frequently remarked that her upbringing had left her with the “feeling of belonging nowhere”. While she was privileged in one way, she was also othered as a woman in South Africa, causing her suffering in her own way. Stern travelled extensively throughout her life, visiting countries including Zanzibar, Congo, and India. In 1926, Stern married Johannes Prinz, her former tutor, and they were divorced in 1934.

In 1922, she had an exhibition in Cape Town; contrary to the norm when South Africa was under British rule, she painted black bodies. The show was raided by the police because it was considered morally wrong under the “Colonial Race Rules’ imposed by the British colonialists. Stern then began to look at the “other races”, the black body, as her focus. She travelled the African continent – this exhibition’s work was painted in her Congo period.

Irma Stern, Watussi Woman in Red, 1946. Oil on canvas. Courtesy private collection, South Africa. Images courtesy of JCAF. Image courtesy of JCAF.

The work exhibited is a portrait of a young woman dressed in red, set against a lush yellow background, entitled ‘Watussi Woman in Red’ (1946). Stern does not name her sitters, but in this case, we know it is Princess Emma Bakayishonga, sister of King Mutara III Rudahigwa (1912–1959), as there is a photograph of her in the exhibition. The woman is sitting in regal repose with a hint of vulnerability. She casts her eyes sideways, avoiding the direct gaze, which would be inappropriate within the traditional context. The colours and brush strokes are bold and colourful.

Here you have three painterly languages of the three woman painters. All of the paintings are about the construction of identities. There has been a misreading from Western feminism of the cultural codes, norms, and practices within particular cultural groups and societies within the Global South. The idea of the feminist gaze within the South is that it is inappropriate for a woman in that cultural context to gaze outside the frame. There is something specific about the cultural norms: you can’t impose current views on the norms of a society that has existed for generations. These were very progressive radical women; they were emancipated; they were active; they were travelling and pioneering; they were selling work; they were having affairs, and they were powerful women in their own right; they could make choices and voice their opinions.

The curatorial approach of the exhibition has been carefully considered, and the design of the presentation clearly threads the narrative and, consolidates the experience and contextualises the experience of the viewer.

Suzette Bell-Roberts is Co-founder and Digital Editor of ART AFRICA magazine.

The exhibition closed on 22 February 2023. For more information, please visit JCAF.