A throw of the dice will never abolish hazard, Mallarme remarked. A game of chance cannot override chaos.

Portrait of Mongezi Ncaphayi. Photographer: David Altman

This conclusion, which will surely irk those in love with fixed origins and absolutes, is profoundly relevant now that we have returned to abstraction as the critical index of our times. Bereft, at a terrible loss for meaning, overwhelmed by the moronic noise of outrage, the moral tedium of revisionist purpose, more and more we find ourselves peering into the unknowable and unknown. Instead of subtraction we value abstraction.

Mongezi Ncaphayi, artist in residence at the Cape Town Art Residency in Woodstock, Cape Town, soon headed to Southern France, is one of the new breed of painters who draw their inspiration from the great early abstract modernists – namely Klee, Kandinsky, Miro. While drawn to Mediterranean and Southern African light, the oozing quiet of the countryside, Ncaphayi remains steadfastly urban. He loves geometry, which, according to the American poet, A.R. Ammons, nature abhors. Squares, in particular, are a passionate interest, as framing devices and as negative spaces. Our built environment is wholly informed by geometry. In particular, Ncaphayi is drawn to ‘structures in construction’, buildings in progress, or delapidated and scaffolded… ‘a staircase in a certain light’… ‘dirty walls, stained floors’… the ‘processional movement’ of Platonic solids, shapes seen in concert, which inform and lend form to the miasmic ground of the world and his paintings.

Acrylic ink, acrylic paint on cotton paper. Photographer: Nicole Clare Fraser. © Mongezi Ncaphayi

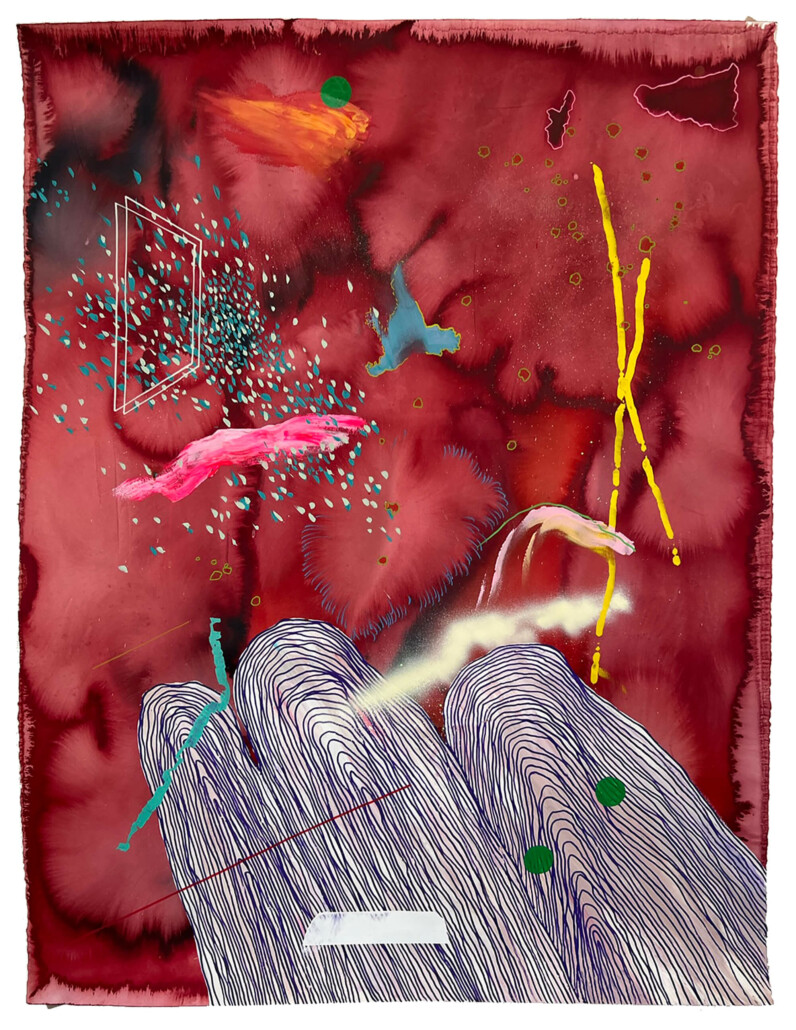

As a boy, Ncaphayi enjoyed drawing ‘packaging boxes piled up’, ‘basic things, basic shapes’. Striped clothing proved a curious consolation – a gridded life in an otherwise uncontrollable world. The processional squared windows of a building, reflective, aglitter… lines loose, thick, soft… are sights seen, absorbed, inhabited, which are then translated into paintings. His favoured medium? Acrylic markers, inks, paints, masking tape to delimit sharp forms. Returning to Mallarme’s formulation, it is the choreography of form and formlessness, solidity and liquefaction, perceptible certainty and flux, which is the artist’s energy field and engine room. Colour too plays its part – the life and hue of flowers in particular. In short, ‘anything and everything’ organic and inorganic.

However, if Kandinsky, Klee, and Miro are easily detectable sources, it is improvisatory music – sound – which proves an even greater inspiration. Keith Jarrett was a childhood inspiration – Ncaphayi owns his father’s cherished LP – in particular, Jarrett’s epically lengthy compositions that fall in and out of harmonic sense, that allow for volume, great drops and rises in sound, that are geological in their groans and howls, pleasures and pains, larval, volcanic – aleatory. Another great inspiration is the saxophonist Pharoah Sanders, who, unlike Jarrett, is no technical wizard, but possesses ‘a great deep feeling’. Somatic, ‘deeply introspective, softly melancholic’. Yet another great influence is another saxophonist, Benny Golson, who, for Ncaphayi, is a brilliant ‘arranger’ of music.

Ncaphayi first stumbled upon the word, ‘arranger’, on the sleeve of an LP. Far more than composer or impresario, this workaday word came to inform what he does when he paints – he arranges elements soft and hard, thick and thin, solid and viscous. It is the tension generated by this interplay that allows for sensation and apprehension. The first is far more significant, because its source lies in emotion, without which an artwork will not emerge, and any reason for being would prove null and void.

Acrylic ink, acrylic paint on cotton paper. Photographer: Nicole Clare Fraser. © Mongezi Ncaphayi

Studying the ground of Ncaphayi’s paintings, it is their larval and aqueous quality that is unmissable. The tones are deliberately fudged, rendered glaucous. That said, they are also eruptive. I’m reminded of Nietzsche’s line about ‘dancing on a volcano’, of some latent hazard. This churning ground is then worked over in a series of segregated and splayed movements in which the artist’s geometric forms emerge. No attempt is made to perspectivally merge foreground and background. Rather, it is their dissonant relation that counts. This is because Ncaphayi is not interested in narrating a meaning, holding the viewer’s hand. What is seen and experienced is, paradoxically, both soothing and discordant. All importantly, what is seen and felt is abstract, for despite Ncaphayi’s fascination with the world all about – the serialised shapes, negative space, erection and dilapidation of our built environment – these observations must be further transformed, so that what we are finally witness to is the hazardous interface of chance and chaos.

It is unsurprising that Ncaphayi is also a gifted saxophonist, a great lover of music, and that it is this great love in particular that informs his art. A case of synaesthesia? Of one medium merging into another? Or an intuitive choreography? If improvised music is the greater inspiration, it is because it is ‘spontaneous, not too safe’, ‘because it is played from the heart, a kind of breathing’. This physiological grasp of sound, and its translation into paint, is, finally, the critical matrix which informs Ncaphayi’s art.

Acrylic ink, acrylic paint on cotton paper. Photographer: Nicole Clare Fraser. © Mongezi Ncaphayi

I began by alerting the reader to the inescapability of hazard, the illusory nature of discernible forms. I also pointed to the fact that today we have lost all true certainty, that the urgencies of our times are merely an hysterical surplus in the face of all we are rapidly losing – such as our fundamental Reason for Being. Lost, unclear, unfocused, uncertain, it is unsurprising that we will find in abstract art our greater consolation. In this vital regard Mongezi Ncaphayi has a valuable role to play. His painterly practice allows for the delicate calibration of form and formlessness. He resists acidic colour and hysterical noise, preferring the silences and sounds of a bearable and easeful life. No angst, no rage, permeates his paintings – other than the eruptive larval nature of a painting’s ground, its latent and subterranean forcefield.

In terms of their improvisatory musicality, I’m reminded of Debussy, or latterly, of Moses Sumney, artists who are elegant, soft, gentle, in their responses to life’s woes and beauty. The aural worlds which they arrange find their visual counterpoint in the gentle sparkle and roiling churn of Ncaphayi’s paintings.

For more information, please visit the Cape Town Art Residency.

Ashraf Jamal is a Research Associate in the Visual Identities in Art and Design Research Centre, University of Johannesburg. He is the co-author of Art in South Africa: The Future Present and co-editor of Indian Ocean Studies: Social, Cultural, and Political Perspectives. Ashraf Jamal is also the author of Predicaments of culture in South Africa, Love themes for the wilderness, The Shades, In the World: Essays on Contemporary South African Art, and Strange Cargo: Essays on Art.