An exquisitely carved ivory elephant tusk, a masterfully cast brass commemorative head of an oba (king) and an iconic brass and copper hip ornament from the historical Kingdom of Benin’s Edo period (16–19th Century) in present-day Nigeria are among the court art treasures in an unmissable provenance research exhibition and enquiry, ‘Pathways of Art: How Objects Get to the Museum’ at the Museum Rietberg Zürich (MRZ). A rich collage of archival material displayed alongside the artworks, including colonial photographs and sales receipts, reconstructs their provenance – their history of ownership.

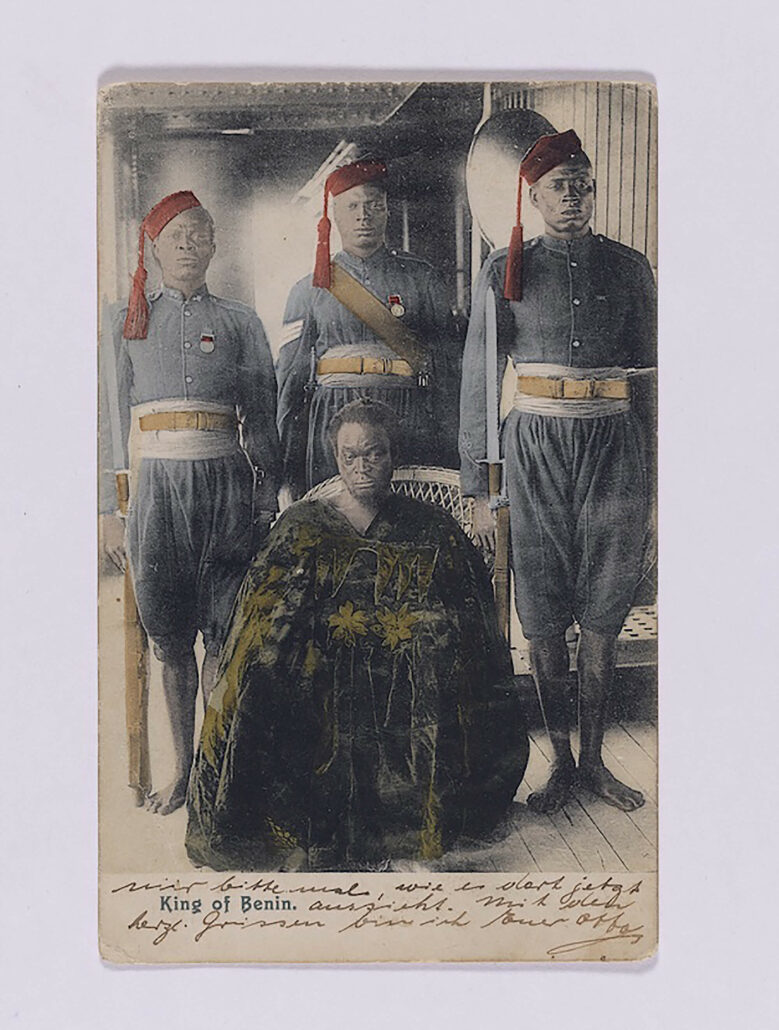

Jonathan Adagogo Green, postcard of Oba Ovonramwen on board the yacht “Ivy” on the way to exile, Nigeria, Benin City, after February 1897, picture postcard, Museum Rietberg, Zürich, 2020.617, purchased with funds of the Rietberg Circle

Provenance: […]; 2005–2020, Christraud M. Geary

The findings of a recently concluded landmark up research enquiry by the Swiss Benin Initiative (SBI), a key feature of the exhibition, show the three artefacts are among 21 objects directly linked to Britain’s 1897 military invasion against the kingdom’s capital, Benin City in the Benin collections of eight Swiss public museums. Burn marks on the tip of the carved ivory tusk which formed part of an ancestral altar, provide evidence of their violent uprooting. A post-conquest colonial photograph of British soldiers amidst a stockpile of looted Benin artworks offers further proof of their plunder. Another photograph of the kingdom’s then ruler, Oba Ovonramwen Nogbaisi (reign: 1888–1897) on his way to exile in Calabar on the British yacht HM Ivy, underscores the invasion’s political and cultural tragedy. As well as the loss of many lives and razing to the ground of Benin City, 10,000 artworks are estimated to have been seized during the military assault, depriving Nigeria of its record of antiquity.

As well as the Benin artefacts and others from elsewhere in Africa, ‘Pathways of Art’ features a striking array of art treasures from the MRZ’s other permanent collections of non-Western art linked to the European colonial era. These include art from Oceania, North America, pre-Columbian cultures, and West, East and Southeast Asia, including China, Japan, and India. Creatively displayed across 20 individual stations, the artworks and documentary material exhibited alongside them convey compelling stories of their multifaceted encounters on their journeys to the Swiss museum.

As part of the ‘Pathways of Art’ project, the MRZ, Switzerland’s only museum of world art, is commendably examining how its collections of non-Western artefacts arrived at the museum. The exhibition describes the various routes they took to get there, the modifications in meaning they underwent, including their aestheticisation and musealization, and their different encounters and connections between individuals, institutions and countries. Established in 1952, MRZ is known for the quality of its non-Western art. Its founding collection was donated by German banker Eduard von der Heydt, a naturalised in Switzerland.

Looted in 1897. Edo designation: Ama. English designation: Relief Plaque Showing an Oba Holding a Rattle in his Right Hand. 16th/17th century, Brass, 9 x 19 x 45.5cm. Courtesy of Museum der Kulturen Basel.

SBI Enquiry/Kingdom of Benin Collections

The SBI enquiry (Benin Initiative Schweiz, BIS) is a critical component of the ‘Pathways of Art’ provenance research endeavour to recognise the extensive looting of Benin artefacts in Britain’s 1897 “punitive expedition” against Benin City and their contested ownership and retention in Western museums. The 2-year enquiry was carried out in collaboration with the Benin Dialogue Group (BDG) and funded by the Swiss Federal Office of Culture (FOC),

Established in 2007, the BDG has opened an exchange between international museums with historic Benin objects in their collections and Edo State, where the new Edo Museum of West African Art (EMOWAA) in Benin City, designed by the Ghanaian-British architect Sir David Adjaye is under construction. The museum will partly house repatriated Benin artefacts. The SBI brought together eight Swiss public museums under the MRZ’s leadership. The aim is to shed light on the contexts in which they acquired their Benin collections in the colonial past and to understand Switzerland’s role in the trade of artworks looted from Benin City during the British military assault.

Involving a large team at the MRZ and curated by Dr Michaela Oberhofer with provenance research led by Esther Tisa Francini, ‘Pathways of Art’ has been extended to April 2024. The project, linked to various ongoing research and collaborative projects, includes those in the context of the broader reflection to decolonise Western museums. The eight Swiss public museums which participated in the SBI and the respective number of Benin artefacts in their collections include Museum der Kulturen Basel (MKB, 21); Völkerkundemuseum der Universität Zürich (VMZ, 18); Musée d’ethnographie de la Ville de Neuchâtel (MEN, 18); Museum Rietberg Zürich (MRZ, 16); Musée d’ethnographie de Genève (MEG, 9); Kulturmuseum St. Gallen (KMSG, 8); Bernisches Historisches Museum (BHM, 3) and Museum Schloss Burgdorf (MSB, 3).

The SBI is a benchmark among museum provenance research as it was initiated by the Swiss rather than following a repatriation claim from Nigeria and was collaborative. As the contentious issue of looted artefacts and where they belong continues to convulse the museum world, the eight participating museums draw instead on ethical guidelines established by the International Council of Museums (ICOM).

These include provisions 6.1, 6.2 and 6.3, which assert that state museums should promote the sharing of knowledge, documentation and collections with museums and cultural organisations in the countries and communities of origin; that they should initiate dialogue for the return of cultural property to a country or people of origin, and that museums should, if legally free to do so, take prompt and responsible steps to cooperate for the return of the objects that were acquired through violent actions during the colonial time or through violation of international and national conventions.

“Since 1986, the ethical guidelines of the International Council of Museum’s (ICOM) have set the standards for dealing with unlawful acquisitions made during the colonial era. Most important for us are the close relationships with the countries of origin from which our collections come. Within the framework of this dialogue, we are certainly open to any discussion concerning the future of the Benin collections in Switzerland,” says Tisa Francini.

Additionally, the SBI adopted the standards on the post-colonial provenance research developed by the German Museums Association in 2021 and the guidelines on the provenance research on colonial collections elaborated by the Swiss Museum Association in 2022. Tisa Francini added that the importance of ‘Pathways of Art: How Objects Get to the museum’ in which the Benin antiquities were of primary significance for its development is that it goes beyond curatorial, collection-related storytelling and presentation of collections for the future.

“Provenance research is the starting point for raising the questions of unlawful acquisitions. It comes with a critical consciousness of how many political, economic and religious histories lie within a museum collection,” Tisa Francini adds.

Significantly, as part of its commitment to the growing decolonising museums’ practice which emphasises working collaboratively with external partners to ensure museums are aware of the effects of the legacy of colonialism, Michaela Oberhofer explained that the SBI team was diverse. As well as the BDG, other external partners include Nigeria’s National Commission for Museums and Monuments (NCMM) headed by Professor Abba Isa Tijani, Dr Alice Hertzog, an anthropologist, and Dr Uzébu-Imarhiagbe, a Nigerian historian based in Benin City.

“The SBI is the first joint project at the national level, involving several collections from different museums in Switzerland, in both its French and German-speaking regions,” she explained.

The findings of the SBI enquiry into the provenance of the Benin objects have recently been published in a report, ‘Collaborative Provenance Research in Swiss Public Collections from the Kingdom of Benin’ (written by Alice Hertzog & Enibokun Uzébu-Imarhiagbe and edited by Michaela Oberhofer & Esther Tisa Francini). The report was formally handed over to a Nigerian delegation at the Swiss Benin Forum in Zurich recently. Professor Issa Abba Tijani, Director of Nigeria’s National Commission for Museums & Monuments (NCMM), Prince Aghatise Erediauwa, the brother of the current Oba of Benin, Baba Madugu, Ambassador of Nigeria in Bern and Corine Mauch, the mayor of Zurich attended the forum.

The SBI findings show that as well as the 21 Benin objects definitely looted during the 1897 British military invasion, 32 are highly likely to have been looted, 16 unlikely to have been looted, and four objects were not looted through it.

The breakdown of the 21 definitely looted category includes MKB (13); MRZ (3); MEG (2); MEN (1), and KMSG (2). Of the 32 objects highly likely to have been looted, the figures are VMZ (14), MRZ (8); KMSG (6); MKB (3) and MEG (1). The itemisation of the 16 Benin objects unlikely to have been looted are the MKB (4), MEG (4), VMZ (3) and MRZ (2).

In line with the shift towards greater transparency and accessibility, the SBI report is publicly available on the MRZ website.

Colonial Pillage

As the SBI research findings highlight, the kingdom of Benin, ruled by eminent monarchs, was at its most powerful under the reign of Oba Ewuare the Great in the 15th Century. It declined, losing power in the 1800s. The invasion and capture of Benin City by British military troops armed with superior firepower in February 1897 constituted an unprecedented act of retaliation. It has turned the crushing of the once-thriving Kingdom of Benin and its iconic artefacts into emblems of Africa’s struggle for its plundered cultural heritage.

In his book, The Brutish Museums (Pluto Press), Dan Hicks argues that the ultra-violent pillaging of African art treasures through “punitive expeditions” represents a seminal moment in British extractive corporate colonialism against African rulers resisting the free-for-all under the guise of protectorates and treaties. Their real aim, he asserts, was to advance British colonial territorial expansion and corporate interests while spinning the old trick that they could do whatever they liked to punish their victims because they deserved it.

The attack on the Kingdom of Benin includes control of the rubber and palm oil trade through the Royal Niger Company. Chartered by the British government, it became part of the United Africa Company in 1929, which came under Unilever in the 1930s and continued to exist as its subsidiary until 1987.

Highlighting their historical roots and the structures that supported their establishment, Western ethnological museums, Hicks contends, played a critical role as cutting-edge ‘weapons of empire’ proffering contradictory propaganda, and includes celebrating the mastery of looted art treasures while simultaneously denigrating the advanced non-Western cultures that produced them.

Internationalisation of Art Dealing in Benin Artefacts

Following the sacking of Benin City in 1897, some looted Benin artworks, known collectively as “Benin Bronzes” (some are made of ivory, wood, terracotta and other materials), were distributed among military expedition members. Queen Victoria was also a benefactor. Many others were sold at auction in London, making auction houses, including Stevens Auction House and Sotheby’s, critical players in bridging the gap between the Benin objects’ military looters and subsequent art collectors. Today, the Benin objects are scattered across museums, institutions and private collections worldwide. The most extensive collections are held in the British Museum in London and the Ethnological Museum of Berlin.

Michaela Oberhofer points out that most African objects entered museums in the Global North before 1960 in the general context of power inequality between colonised and colonialists.

“However, these transfers were of different kinds, ranging from gifts to exchange to purchase. But despite the power asymmetries, there was also agency and participation on the African side in certain transfers. Moreover, artists in Africa began producing works for the Western market from very early on. Earliest examples include the Sapi-Portuguese ivory carvings, which were produced on the African coast for European courts as early as the 16th Century,” she added.

As well as removing ambiguity about how many of the Benin art objects ended up in the eight Swiss museums, the SBI provenance enquiry has unearthed a wealth of information about the ancient Kingdom of Benin and its iconic artworks and about the highly skilled artistic guilds, which produced them, and the diverse range of actors involved in their ownership history and dispersal worldwide.

Looted in 1897. Edo designation: Uhunmwu Elao ọghe okhaimwen. English designation: Commemorative Head of a Dignitary. Acquires by the museum before 1901. Wood, brass plate, copper sheet, 52 x 20cm. Courtesy of Museum der Kulturen Basel.

As its findings further testify, from the 15th Century onwards, the Kingdom of Benin had a long history of exchange and trade with the Global North, especially with the Portuguese (as the carved ivory tusk in the exhibition embeds) with whom it traded metals, pepper and enslaved people. Many of the Benin objects within the kingdom were used in spiritual contexts. They were part of ancestral altars and remembrance practices in Benin City, including sixteen commemorative heads of kings and chiefs (Uhunmwu-Elao) and queen mothers (Uhunmwu elao ọghe Iy’ọba), some of which are older, and others more recent productions. The Benin objects also served as repositories and archives of historical knowledge and memory.

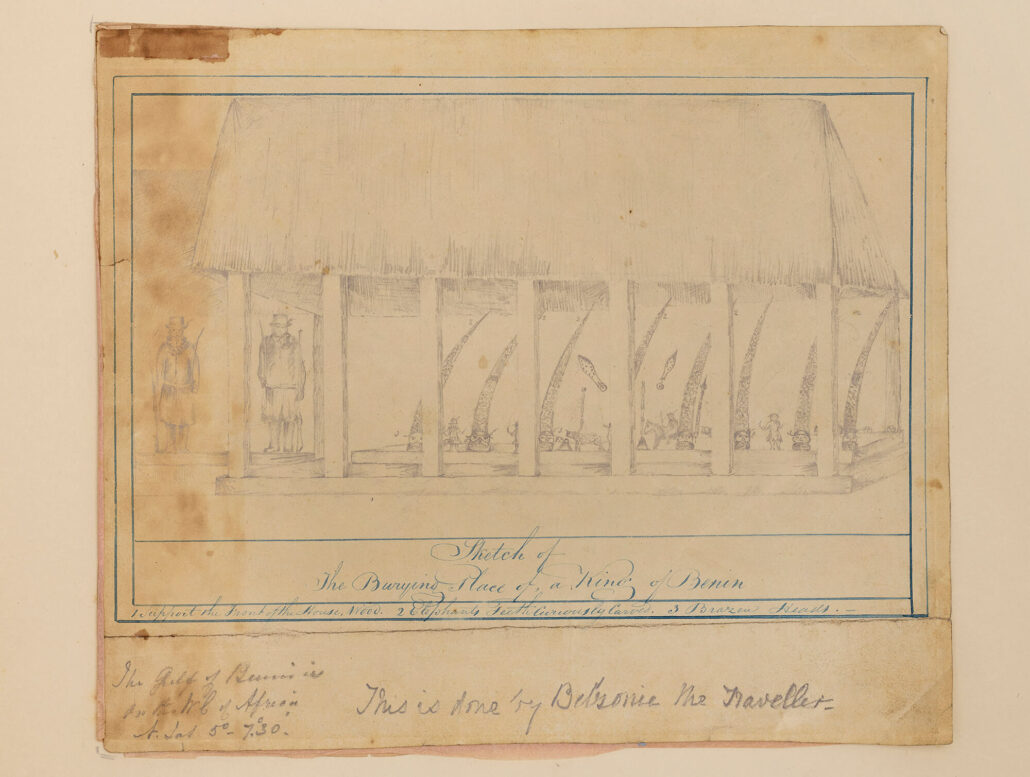

Drawing of an ancestral shrine in the kingdom of Benin, attributed to Giovanni Battista Belzoni (1778–1823), 1822/23, paper, 23 × 27 cm, Museum Rietberg, Zürich, 2020.106, purchased with funds of the Rietberg circle

Provenance: […]–13 July 1977: Christie’s London, Lot. 176; John Hewett, art dealer, London (1919–1994); […]–January 29, 2020, Lempertz, Art of Africa, the Pacific and the Americas, Brussels, auction no. 1147, lot 103

Speaking at the SBI forum, Prince Aghatise Erediauwa said the initiative is the first time collaborative provenance research has been undertaken on the Benin artefacts. He added that usually when Western museums carry it out, it is on their terms. “We’re all familiar with the narrative of why some museums want to hold on to looted cultural heritage rather than doing what is proper instead of out of self-interest. We must give credit to the Swiss, not only in being transparent but also for the collaborative nature of the initiative and for setting an example,” he said.

Expressing the impact of their dispossession on the Benin people and culture, he added that the artefacts’ function goes well beyond artefacts.

“The Benin objects’ religious and ritual role cannot be overemphasised. When I see these bronzes on display in glass cases in museums, it’s difficult for me to hold back emotions. We still have many of the shrines from which these objects were taken that have spaces in them. The Oba knows why these shrines have been left empty. It is in the hope that one day, the bronzes will return and fill them.”

Although Switzerland never had colonies, as the SBI report findings show, Swiss actors, motivated by socio-economic, scientific and religious interests, were active in the colonial enterprise. Michaela Oberhofer said that within the African collections of the participating SBI Swiss public museums, the Benin pieces make up only a tiny part of the total collection of other museums outside Nigeria and that they are, nevertheless, of great importance in African art history due to their considerable age and artistic quality. Wooden objects from Africa usually date from a more recent past due to climatic conditions. That Benin artworks made of metal are exceptionally durable and date back to the times of the historical Kingdom of Benin in the 15th Century and earlier.

“Transparency and open communication about the Benin collections have been central issues for the SBI from the start,” Oberhofer explained. “We have regularly published our findings on the joint SBI website hosted by the Museum Rietberg including lists of all objects, press releases, reports on trips and workshops, and films about the SBI. Findings of other museums involved in the SBI are also regularly published on the respective websites,” she said. “The mutual exchange of knowledge and documents is also essential in the cooperation with our Nigerian partners, and the SBI members have always immediately shared their latest findings with them. The SBI cooperates with Digital Benin. All objects including archival material held by the SBI museums are or soon will be accessible worldwide on this digital platform.”

As well as the Benin objects in the eight SBI participating public museums, Switzerland is home to some of the world’s most prized private collections of African art. These include the Barbier-Mueller and Baur museum collections in Geneva and Abegg in Riggisberg. Explaining the likely impact of the SBI enquiry on non-public collections, Esther Tisa Francini said artworks with an unresolved provenance held in Swiss private collections would probably disappear from the art market entirely for a while.

“The restitution debate has had a considerable impact on the art trade. It drives provenance research, but, at the same time, it also creates a shadow market. Without knowing the outcome of our dialogue with Nigeria, we cannot speak about the impact of the findings on the museums’ collections,” Tisa Francini added.

Notably, the SBI research findings show that, unlike museums in the UK and Germany, Switzerland acquired its Benin objects over a long period, with the first acquisition taking place in 1899, two years after the British military campaign against Benin City, to modern objects which only entered the MRZ inventory in 2022. The Museum der Kulturen Basel (MKB) was the only Swiss museum procuring ten objects immediately after the 1897 military expedition.

Highlighting the aesthetic appeal of the Benin artworks (and other African artefacts), which went on to influence several modern European art movements, including Cubism and Dadaism – among Swiss and Swiss-based art collectors – the SBI report has identified the involvement of 71 actors in the circulation of the eight participating Swiss public museum collections. Most were men, art dealers and collectors, followed by academics, museum professionals and armed forces. The two most prominent among the taste-making actors in the African art scene in Switzerland were the Swiss collector Han Coray (1880–1974) and the anthropologist Prof. Hans J. Wehrli (1871–1941), who became the first director of the Völkerkundemuseum der Universität Zürich (VMZ,1909–1941).

Coray amassed an impressive collection of around 2,400 artefacts from Africa without visiting the continent and was among the first to exhibit African art objects as art rather than tribal artefacts in Switzerland. Following the seizure of his collection by the Schweizerische Volksbank in 1931, Wehrli acquired a large part of the collection of African objects, including 30 Benin objects, with the help of his longstanding scientific assistant Elsy Leuzinger (1910–2010). These were sold to Swiss museums and private collectors, including the 30 Benin objects currently in the MRZ, VMZ and KMSG.

Looted in 1897 Aken’ni Elao. Carved Elephant Tusk, 18th century, Ivory, 114.7 x 12.5 x 15cm. Courtesy of Museum Rietberg Zürich.

Another key duo is Jean Gabus (1908–1992) and Peter Rufus Osunde. Gabus purchased 17 objects from Osunde, among the few Nigerian actors involved in the trade, in Lagos in 1963. A professor of art at the School of Art Design and Printing at the Yaba College of Technology, he was also a unionist, artist and art dealer. Other notable players in the trade in Benin artworks include William D. Webster (linked to 13 objects), Johan Gustav Umlauff (4 objects) and the German-Swiss banker, art collector and patron Eduard von der Heydt (4).

SBI research findings on the sublimely carved elephant tusk (Edo designation: Aken’ni Elao), part of Museum Rietberg Zürich (MRZ)’s collection, show it was created in the 18th Century by the Royal Ivory-sculptors Guild (Igbesanmwan) and commissioned by the Royal Palace of Benin. Paperwork reveals that, around 1900, it may have been in the hands of Arnold Rudyard, a collector and engineer with Elder Dempster & Co or George William Neville, an agent with the same company. Between 1908 and 1928, the tusk was possibly owned by William John Davey, the manager of Elder Dempster & Co. The tusk appears to have remained in the hands of the Davey family, including Lydia, Harold, and Florence E. Davey, until 1962. In 1962, it was sold at auction through Sotheby’s Auction House in London, after which the object came into the ownership of Kenneth John Hewett, an art dealer in London. It then belonged to another art dealer, Ernest Winizki and was purchased by the MRZ in 1993.

Looted in 1897. Edo designation: Uhunmwu-Elao. English designation: Commemorative Head of an Oba. 16th/17th century, Brass, 29 x 21cm. Courtesy of Museum der Kulturen Basel.

As for the imposing brass commemorative head of an oba (Edo designation: Uhunmwu-Elao), currently part of the Museum der Kulturen Basel (MKB), the SBI research findings show that this was commissioned in the 16th/17th Century from the Royal Bronze-casting Guild (Igun Eronmwon). After being looted from the royal palace in Benin City during the British military occupation in 1897, it was owned until 1899 by William Webster, a London art dealer, and then purchased by the MKB in 1899 with funds from Elisabeth Sarasin-Sauvain.

Looted in 1897. Edo designation: Uhunmwu-Ẹkuẹ. English designation: Hip Ornament. 18th/19th century. Brass, copper. 17.5 x 11 x 5cm. Museum acquired artefact before 1945. © Musée d’ethnographie de Genève, Johanthan Watts

SBI research findings on the brass and copper hip ornament (Edo designation: Uhunmwu-Ẹkuẹ), currently part of the Musée d’ethnographie de Genève (MEG) collection, reveal that this was commissioned in the 18th/19th Century from the Royal Bronze-casting Guild (Igun Eronmwon) by the Royal Palace of Benin. Following its looting in 1897, it was sold at auction on 4 July 1899 through J.C Stevens Auction House in London for £5.10.00. Between 1899 and 1902, the bronze may have been in the hands of the London art dealer William D. Webster. It was sold at auction again on 3 June 1902 through Stevens Auction House for £7.10.0. The date the MEG acquired it is unknown, but believed to be before 1945.

Moving Forward

The SBI provenance research findings inevitably give momentum to Nigeria’s decades-old struggle to reclaim the looted Benin antiquities, which began soon after the 1897 British invasion and heightened in the 1930s colonial era, occurring in 1960 when the country gained independence from British colonial rule. Cultural heritage, one of the most visible manifestations of a people’s unique identity, became part of pan-African nationalist movements. It gathered momentum again in 2007 with the establishment of the Benin Dialogue Group (BDG) and other initiatives.

More recently, the SBI and BDG have gained impetus from the ‘Black Lives Matter’ and ‘Decolonize Museums’ movements, which have put pressure on Western museums to repatriate stolen African artefacts and root out “art washing” – the practice of using art and culture to launder ill-gotten gains and predatory practices in Western museums.

Another spur was provided by the 2018 report by the French art historian Benedicte Savoy and Senegalese writer Felwine Sarr, ‘On the Restitution of African Cultural Heritage, Toward a New Relational Ethics’. The report offers solutions to French President Emmanuel Macron’s call in 2017 to return looted African artefacts in French museums within five years and appeals for transparency of museum inventories of art acquired in the colonial context. It asserts that 95 percent of Africa’s cultural heritage remains outside the continent.

The SBI findings inevitably raise critical questions, including where artefacts acquired in the colonial context ultimately belong and how best to engage with them. Repatriation advocates argue that returning illegally gained objects to their countries of origin contributes to addressing historical wrongs. However, its opponents, including the British Museum contend that as universal, encyclopaedic museums, Western museums holding such objects help celebrate and promote them as part of humanity’s heritage. Such artefacts, they argue, whether acquired by purchase, gift or partage, have become part of the nations that house them and that as ‘universal museums’, they provide a valid and valuable context for them.

Commenting on the landmark SBI inquiry and its findings, Professor Abba Isa Tijani, Director of Nigeria’s National Commission for Museums and Monuments (NCMM) said its approach is commendable and interesting. Not only because it was formulated by the Swiss themselves, but also, he added, because the public was carried along with it and they can engage with it. Asked if Nigeria will formally be asking for its Benin objects back from the eight SBI participating Swiss museums in view of its significant findings, he said the aim is to have the objects returned to Nigeria.

“We don’t want to empty their museums. So that’s why we want to go into partnership with them so that we can leave some objects on loan. I want to emphasise this, there are museums that don’t have Benin bronzes and there are some with just a few. So, the importance of partnership is to see that even with our own collections back in Nigeria we can be able to give some of these objects on loan. So, the transfer of ownership is key. After that, we can discuss how many objects we want to leave behind and for how long. I think the aspect of partnership and having a common agreement is key,” he said.

Asked if their return should be accompanied by some form of monetary compensation as the Benin objects were taken as a result of an invasion on a peaceful empire, ransacking it and destroying its cultural heritage, he said, a partnership as agreed with the Swiss SBI participating museums, is beyond financial compensation.

“I know there’s a lot of emotions, pain and uncertainty left behind from the looting. But today we’re looking at getting the artefacts back as the priority. Other things we want to consider at a later stage because we feel that the most important thing is to get back ownership of these artefacts in the first place. We know that our Swiss partners have the capability so we want to see a situation where they can support us in capacity building and exchange of staff. Because that way, they too can learn a lot about Benin culture and traditions,” he added.

He added that what happens after repatriation generally is important which is why the NCMM is looking at it in a comprehensive way whereby once the Benin objects are returned to Nigeria, some of them can be loaned to different museums to avoid creating a vacuum. He said the commission sees a situation where the Swiss too can go to Nigeria to learn more skills and also support it in technical aspects including the digitisation of Benin collections so that Nigeria can easily share them with its partners and audiences across the globe online to promote the cultural heritage of the people of Benin. This he added, would become a mutual engagement for the benefit of institutions within the two countries.

“We believe there are communities who are interested in the cultural heritage of Nigeria who have a special attachment to the Benin collections be it Nigerians or other Africans in the Diaspora and even some local communities in Switzerland and other Western countries because they’ve been seeing these objects for decades. So, we believe that there’s a need for us to give some of these objects on loan. But also, there’s a need to collaborate in areas where we can work together such as in joint research, joint exhibitions, capacity building and other aspects of museum activities” he explained.

Galvanised by the ongoing destruction of ancient sites and art including by Islamic State in the Middle East and Africa, another reason some Western museums say they are reluctant to return looted artefacts is concern over security and storage.

“I think these are some of the gimmick’s institutions that don’t want to engage in repatriation use. They want to find an excuse to hang on to the objects forever which we say is not possible. These museums are global institutions, and we work together to enhance these institutions. We believe that museums in Africa, particularly in Nigeria, are also aware of the growing need for security of our objects. Not just physical security against theft and the rest, but also security in the museums in terms of providing the necessary environmental conditions. We believe that we’re capable of that and that is why we have got far and have started building new museums to house these objects” he asserted.

An example of this, he added, is the Federal government of Nigeria’s approval of funds to expand the existing National Museum of Benin City with a new storage facility and exhibition gallery. “We also have the mandate of the Nigerian Federal Government to build a new museum very close to the palace of the Oba of Benin which will be called the Benin Royal Museum,” he explained.

He added that with over 3,000 staff across Nigeria, the NCMM has the professional capacity to protect its repatriated artefacts and has been collaborating with Western museums including through the Benin Dialogue Group (BDG) for many years. “We’ve been doing joint exhibitions with the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and even the British Museum in London which have given objects on loan. So, I think we have the capability so that shouldn’t be a reason to not return the Benin artefacts,” he stressed.

In response to the slow pace of the repatriation of the Benin artefacts to-date and stolen art generally including that looted by the Nazis and whether a global structure should be put in place to speed things up, Professor Tijani said he’s comfortable with the case-by-case approach being taken by the NCMM.

“This is because, as a country, we need to have enough time to engage with these institutions. When we rush, we’ll be missing quite a lot in terms of collaboration. I think a global approach would be very difficult to achieve because you’d be bringing different countries and different laws together and it would take time to formulate it. I look at our struggle as already globalised because many countries now agree to repatriation because they see other countries doing it. I think this approach can continue, as we are getting results,” he added.

For some advocates of restitution, especially those who see Western museums as institutions of “cultural confinement” direct action, which has a long history of protest against museums and has seen a resurgence in recent years, is justified, in view of the slow pace of returns. Responding to this, Professor Ajani said it is important that advocates of restitution respect institutions that are taking care of the historic Benin artefacts.

“Individuals don’t have the right to go and demand these artefacts. They can agitate for their return but as a government and as a commission, we don’t support it. Individuals trying to take the law into their hands or create some kind of impasse with museums and countries, I don’t support,” he stressed.

Responding to questions about how Nigerians will feel when the Benin artefacts are repatriated from Switzerland, Professor Tijani said many have already expressed their pleasure at seeing the recent return of some objects from several other Western countries.

“The return of the Benin bronzes is actually happening physically which is why we’ve assured Nigerians that we’re going to have a special exhibition for them so they’ll be able to visit our museums and see these objects tangibly and appreciate them. In particular, the Benin people have really expressed their emotional feelings in terms of their spirituality and position of the Oba and to show that their empire is becoming more vibrant again. Also we’ll continue with practice of producing the Benin bronzes which has not stopped by the way, which will encourage Nigeria’s youth to know more about their cultural heritage as well,” he added.

Although its widely known that most Benin artworks in Western museums were looted during the 1897 British military expedition, for Annette Bhagwati, the Museum Rietberg Zürich (MRZ)’s German director, the SBI provenance research enquiry was important for several reasons. As well as being a very interesting and fruitful exchange with colleagues from Nigeria, she said, the joint initiative revealed many important dimensions of the Benin artefacts.

“For example, the emotional value of the Benin objects which here in Switzerland are considered as art but carry completely different meanings to the people of Benin. History inscribed itself in the Benin objects including in their spiritual role. So, this taken together goes much further than the looting of 1897. It situates the artworks in the wider artistic tradition of the court of Benin but also in the Benin history,” she clarified.

For Bhagwati, the SBI’s most critical findings has been clarity on the Benin artefacts.

“Looking at the broad array of objects we have through the SBI provenance research, identifying Benin objects that can be traced back to the ‘punitive’ expedition but also those that are likely or very likely to have been looted where we can’t trace this 100 percent, is important. As part of the iconography of the royal court, they are most likely to have been looted. So having clarity to parts of the collections with our Benin partners is important for discussing the future of the collections,” she added.

As well as removing ambiguity over their provenance, Bhagwati said examining the total collections of Benin objects beyond the 1897 expedition into their broader history embedded in the objects was also important for knowledge production. This includes its many references to the art production and history of Benin beyond 1897 which is present in the objects and the contemporary Benin artists and guilds that have continued the production of Benin objects.

“This broader embedding of 1897 in the wider history and perspective is important for me because we really started to just clarify 1897. But it goes much broader and further. And the other thing to notice and experience was how fruitful collaboration can be. Because not only did different knowledge and knowing come into the open, but also many possibilities that I hadn’t thought of opened up which can go in all different directions,” she said.

Asked if a lot more should be done and more quickly with regard to the repatriation of looted artefacts including the Benin objects, Annette Bhagwati stated that each case is individual. She added that she thinks a lot more should be done to finance provenance research to look into the histories of artefacts because they are very complex. She said more funding should be made into making their stories visible which is currently not in the minds of those providing funding including for shared exhibitions that should take place in both Nigeria and Switzerland.

“In terms of dealing with difficult histories, I think what is sometimes missing is the courage to look at it directly without any other feelings. We look at the facts and once we have those on the ground, then we move forward together. By making this history visible jointly, by discussing it jointly, by dealing with it jointly and jointly finding ways to the future, we can deal with it although you can’t correct it,” she stated.

Asked why many Western museums continue to avoid dealing with the Benin artefacts’ shared, fateful history she said: “Because it carries a lot of guilt.”

“On the political level, it might carry some sort of fears of compensation once you open the Pandora’s box. But I think these steps need to be taken. Switzerland didn’t have any colonies but was heavily involved in the colonial past. I think other museums obviously like those in Britain which was responsible for the 1897 looting are under different political pressures,” she added.

She explained that the history of the Benin objects needs to be discussed within partnerships.

“What I find is that there’s a lot of interest in partnerships, which we’re going to welcome and less in compensation. Interest in common projects for example, commonly funded skills building, expertise and transfer of knowledge on both sides. So rather than general compensation, there’s interest in specific and targeted funding which will be beneficial to both sides,” she added.

As for other museums’ concerns over security and storage, Bhagwati said, first of all, Nigerians have museums and storage but one of their great interests is to collaborate.

“For example, in improving the way objects are being stored. Exchange of knowledge and how it can be done because different museums require different conservation facilities and so to have that exchange and also to collaborate on building this, is important. Secondly, with regards to repatriation, the way we’re discussing it opens up a broad range of possibilities. So, for example in the SBI’s joint declaration, a key word consented on is that of transfer of ownership which can involve the physical return of Benin objects to Nigeria, but it can also be a loan to the museum, so I think there are much more possibilities,” she said.

Asked if the Museum Rietberg Zürich (MRZ) and other SBI participating museums are open to returning the Benin objects in their collections and whether the Swiss Federal government would allow it Bhagwati said the Swiss situation is different from other countries and is a special case.

“In Switzerland although we have the Federal government, the onus on the return of the Benin artworks would be on the municipal and cantonal administrations. That’s why we constructed the SBI declarations. It’s different from Germany and other countries because it’s a bottom-up approach. Now that we have achieved consensus on the transfer of ownership between the eight Swiss SBI participating public museums, it’s now up to the individual museums to talk to their respective cantonal structures. I can say that the city of Zurich is very open, has been very warm and has been following the process and is looking forward to the recently published results of the SBI initiative after which we’ll engage with them,” she explained.

Asked what likely impact of the landmark SBI provenance inquiry will have on other Western museums, Bhagwati said she hopes it will encourage them to be more pro-active.

“I think a lot of hesitation perhaps comes from a fear of not knowing where the journey will lead to. For us, having started the journey and doing the SBI provenance research has been beneficial for all parties involved. This is a wonderful way forward,” she said.

‘The Pathways of Art: How Objects Get to the Museum’ exhibition runs to April 2024.

Santorri Chamley is an experienced multi-media journalist and TV news producer. Her journalism largely focuses on human rights and justice issues arising from the unjust imbalance and power asymmetry between the industrialised North and developing South and political and economic structures put in place for powerful interests at the global and local levels. She does this with a particular focus on Africa and the Diaspora. Experienced at uncovering and reporting international stories, she has produced reportage for a diverse range of international media organisations. These include BBC2 Newsnight, The Guardian, New African, Channel 4, Index on Censorship and CNN International.