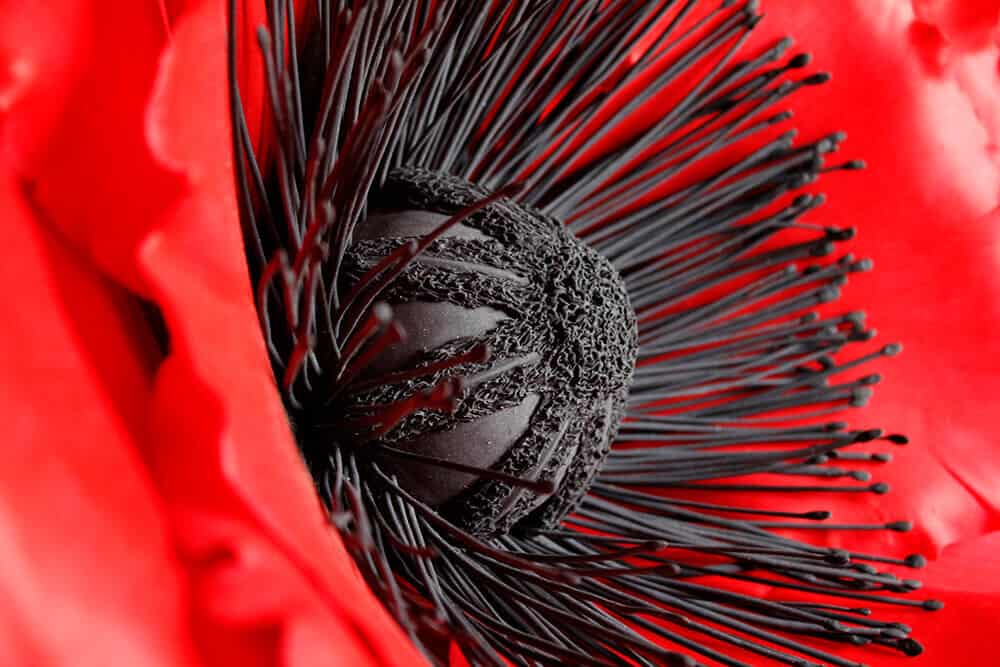

Owanto, Detail of Flowers VI, 2019. UV print on aluminium with cold porcelain flower, 125 x 176 x 17cm. All images courtesy of the artist.

Owanto, Detail of Flowers VI, 2019. UV print on aluminium with cold porcelain flower, 125 x 176 x 17cm. All images courtesy of the artist.

Today, few Ohioans know that, throughout the 1960s and 1970s, James Burt – a physician whose name should maybe not be cited, but words, like time, bear witness – performed what he dubbed “surgeries of love” on over a hundred and seventy women. Those he considered “structurally inadequate for intercourse,” a condition “amenable by surgery,” were upgraded, for the fulfilment of his male counterparts’ pleasure. At the time, the desire to subjugate women’s bodies had a Burt for avatar. In our contemporary reality, however, possessivity takes on different names and shapes. Men invent digital assistants, capable of serving them better. They carry new pseudonyms, although the femininity of the subservient remains: they’re called Alexa, Siri, or Cortana[1].

This year, Cincinnati, in which I used to reside, launched a citywide initiative called Power of Her in celebration of the hundredth anniversary of the suffragettes movement; an offensive, which guaranteed American women’s constitutional right to vote. In my little corner of the Queen city, tucked away in an art centre I dreamed to be for women, I conceived Owanto’s exhibition.

In case her pseudonym had not made that clear, Owanto is a woman. In Myene, her mother’s native language, that’s the word one uses for the feminine kind. This name, she recognized as hers; a simple gesture of acknowledgement we, women, do all the time. We acknowledge each other’s presence, and in so doing, we respond to our existence being in constant jeopardy. When I think of women acknowledging each other, I am reminded of a man I loved, who, when passing another Black man on the street, would nod at him. Your presence is felt, he signified. Reborn as Owanto, the artist salutes her mother, who bore the name, and bows at us all.

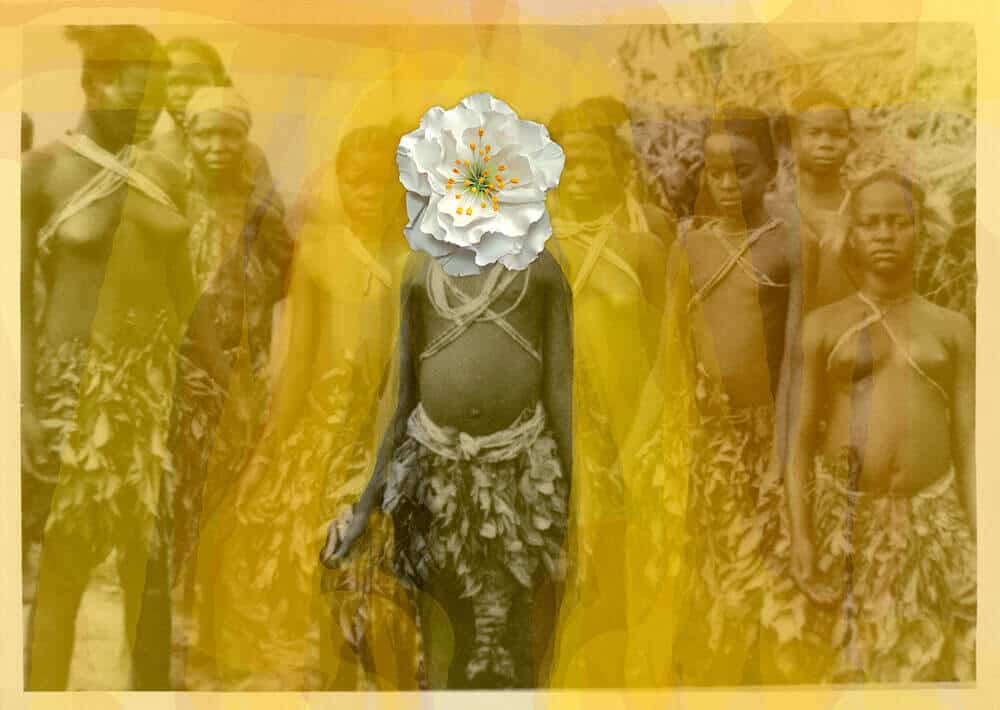

Flowers VI, 2019. UV print on aluminium with cold porcelain flower, 125 x 176 x 17cm.

Flowers VI, 2019. UV print on aluminium with cold porcelain flower, 125 x 176 x 17cm.

A couple of miles away from where I imagine her exhibition, another Black woman, born approximately at the same time, made the same commitment. In 1978, professor and writer Gloria Jean Watkins borrowed her great-grandmother’s name, and became the incredible figure we now call bell hooks. In her essay “to Gloria, who is she”[2] (in Talking Back), she writes: “claiming this name was a way to link my voice to an ancestral legacy of woman speaking – of woman power.”

Akin to bell hooks, Owanto has a history of naming names. She regularly rebels against what the latter considered women’s “pattern of guarded expression.” Her recent Flowers series, which raises awareness about FGM/C (female genital mutilation/cutting), exemplifies this practice. To create the thirteen of photographs, the artist embraced the role of the reporter, digging into the humus of buried family histories, having discovered, in a photo album belonging to her late father, a set of small, disturbing prints. In interviews, she recounts her knee-jerk reaction to the 3 x 4 in. yellowed photographs. Depicting rites of passage, they displayed young women, their legs splayed, frontally shot while they underwent circumcision. Like sun imprinted on the retina, these images stuck. No matter how far Owanto shoved them back in her “forgotten drawer.” What colonial past had been hidden there, under layers of dust? The shadow image of the burn, still present to her mind, forced Owanto to “talk back.” Mixing sculpture and photography, a medium, whose predatory possibilities have already been discussed – it was commonly used by colons to justify eugenic and racist classifications – , the artist looked for a way to reclaim ownership over women’s bodies, and the way their history is told. She associated each photograph with a uniquely crafted porcelain Camellia, that she adorned the print with, as if to stitch back part of the cutout flesh. Reading about Camellia oleifera’s history, the species most prevalent in gardens, I discovered that, in Japan, where its oil is pressed, the flower is used to clean blades and cutting instruments.

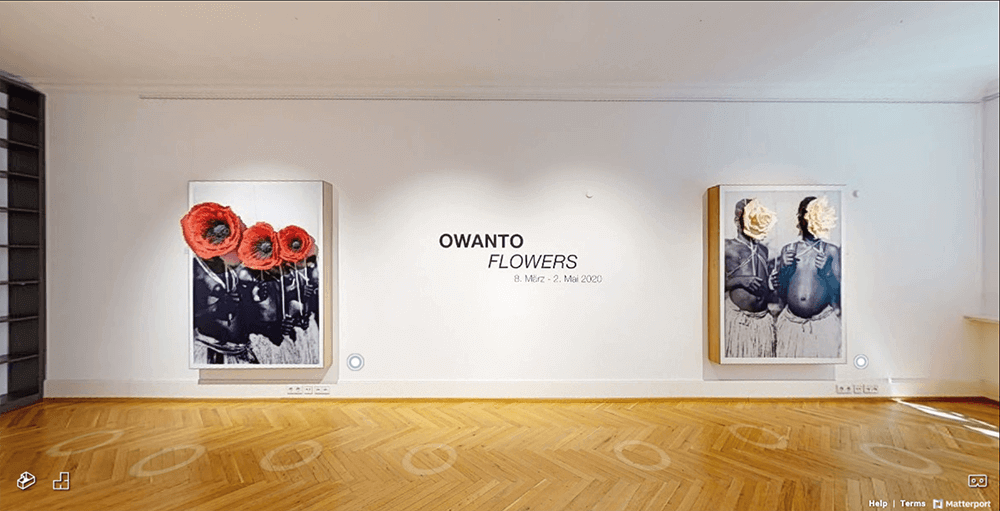

Flowers VI, 2019. One Thousand Voices, exhibition view, Zeitz MOCAA, 2019. Permanent collection of Zeitz MOCAA. Courtesy of Zeitz MOCAA.

Flowers VI, 2019. One Thousand Voices, exhibition view, Zeitz MOCAA, 2019. Permanent collection of Zeitz MOCAA. Courtesy of Zeitz MOCAA.

From the series of thirteen, La Jeune Fille à la Fleur is probably the most striking image. It now permanently rests in the collection of the largest existing African museum, Zeitz MOCAA, in Cape Town, South Africa. Looking at the image, it is not the flower – although yellow, iridescent, placed between the young woman’s legs – that strikes one most, but this hand, that lies there, on her right shoulder – this problematic hand, impossible to read, both firm and comforting; coercive, but that we hope a gesture of support.

This work polarizes critics and thinkers. Because of its content and approach, Owanto’s research triggers. It raises the question of representational justice and artivism, of showing violence inflicted on Black bodies, a tropism that art history is laden with. Maybe because of these concerns, maybe because of personal interest, over the years, I’ve become less captivated by the Jeune Fille à la Fleur. Like the first blinding light, the dark halo imprinted on Owanto’s retina, it will never leave my mind. I can see with my eyes closed. This is the reason why, when imagining the artist’s exhibition in Cincinnati, I chose for the image to not take centre stage. Instead, I favoured another entry point into the work, through sound.

Imagine a block of concrete, with slanted staircases going up and down grey bowels. A figment of Zaha Hadid’s obsession, the museum opens like the belly of a whale. Once inside, your feet take you to the closest corner of the pit, where a descending set of stairs awaits. With each step, oblique to the point of imbalance, luminosity levels decrease. Having reached the entrails’ lowest level, your eyes are accustomed to the shadows. And there, tucked away below the slanted staircase, Owanto’s jewel case rests, protected. From a door, ajar, a thousand voices emerge.

https://soundcloud.com/suzette-bell-roberts/one-thousand-voices-educational-version-cc-license

Often paired with the Flowers, One Thousand Voices, as an immersive sound display produced in collaboration with journalist Katya Berger[3] – the artist’s daughter –, amplifies FGM/C audio testimonies from thirty-five countries, and from women aged fourteen to seventy. Symphonic in the installation, their voices were first recorded on phones, and sent to Owanto via apps, before they were digitally edited and collaged together with the crackling sound of a broken record. The effect the loop creates, is that of an immemorial line of women. Having gone through similar rites of passage, their pain reverberates, at times dissonant, but often in unison, on the empty concrete bowels of the museum.

After years working in art institutions, mostly Western-centered, and often run by men, I became more and more interested in the possibility of relinquishing one’s power of speech. I studied artists, who like Simone Leigh or Maren Hassinger, see themselves as facilitators, furthering other people’s rights by enabling others to speak up. Working on a book about vocal practices, and its use in artivism spheres, I often return to this passage, in which bell hooks talks about her unstoppable desire to speak. It is underlined in my copy of Talking Back: “that speech was to be suppressed so that the ‘right speech of womanhood’ would emerge.” Amongst curators and artists, both – though unevenly – placed in positions of power, visible and audible, those who radically transform the art world are those who step aside and give out the microphone.

In ancient tragedies, there was a material construct for this idea, called the chorus. Made up of non-individualized performers, choruses represented the collective voice in a play. With rare exceptions, their members spoke the lines in perfect unison, expressing the community’s feelings, while commenting on the dramatic action and events. They were the same sex as the main character. This mental image of women chanting behind Euripides’ Medea colours my reading of Owanto’s practice. The “thousand voices” she conjured attest to the chorus’ essential trait: they have us shift between one young woman’s unique experience (represented in the exhibition by the prints’ corporeal presence), and the representation of the multitude, whose varied voices are heard.

Click to view the Virtual exhibition, ‘FLOWERS’ by Owanto at Shakile&Me

Click to view the Virtual exhibition, ‘FLOWERS’ by Owanto at Shakile&Me

Speaking of the “drum” in Critique de la Raison Nègre,[4] Achille Mbembe’s wrote: “rythmes et sons ont un pouvoir de susciter, voire de ressusciter, de mettre debout.” Contiguous in sounds, the Frenchverbs susciter and ressusciter, imply the following: sounds, and by extent, voices, have the power to arouse and to resurrect; they pull us up, they mend, they re-erect. In other words, they repair. Owanto’s chorus too, is a talk back, a beating drum of resistance; one, which enables women to stand up on each of their two thousand feet.

Valentine Umansky is an independent writer and curator.

FOOTNOTES

- For more information about this issue, you may read the article of my friend, wonderful writer, Jacqueline Feldman: <https://www.newyorker.com/tech/annals-of-technology/the-bot-politic>

- hooks, bell (1989) Talking Back: Thinking Feminist – Thinking Black. Boston: South End Press

- The educational 14 min version is available here: <https://www.voices1thousand.com/education>

- Mbembe, Achille (2019) Critique de la Raison Nègre. Paris: La Découverte