The paintings on show in Nigel Mullins’ solo exhibition Caveman Spaceman bespeak a yearning for (as well as aversion to) the Real, which is lost with every hyper-real painting as representation of representation, copy of a copy. Each hyper-real/unreal painting produces the loss of the Real, as well as the loss of the aura of originality and authenticity, at the very moment that the painting mourns the passing away. Mourning produces the very loss that is mourned.

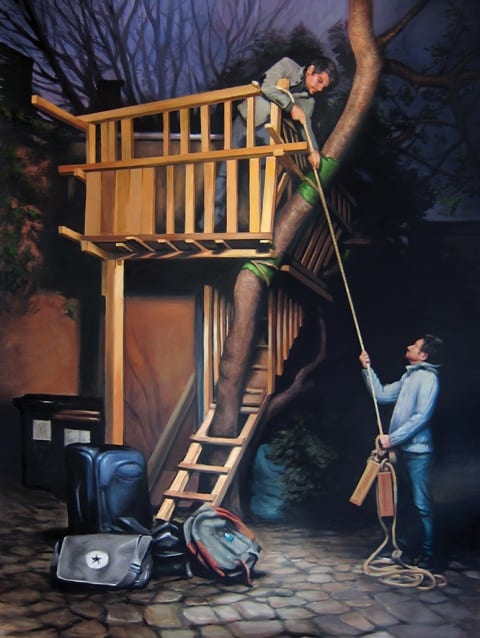

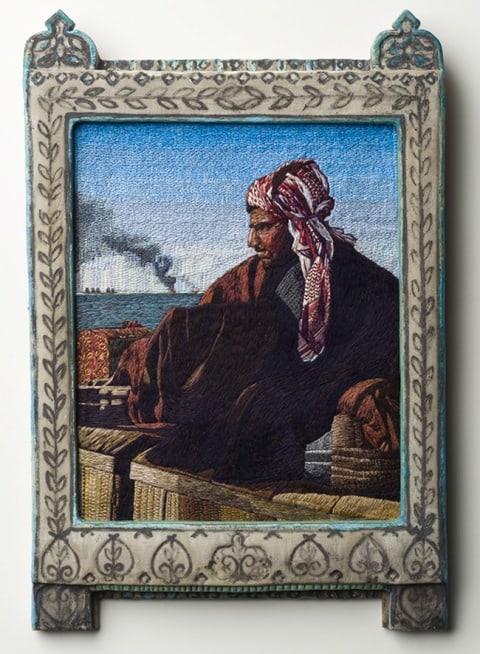

Nigel Mullins Aim To Please, 2008, oil on canvas, 120x180cmThe paintings on show in Nigel Mullins’ solo exhibition Caveman Spaceman bespeak a yearning for (as well as aversion to) the Real, which is lost with every hyper-real painting as representation of representation, copy of a copy. Each hyper-real/unreal painting produces the loss of the Real, as well as the loss of the aura of originality and authenticity, at the very moment that the painting mourns the passing away. Mourning produces the very loss that is mourned.In his essay ‘The Artwork in the Age of its Mechanical Reproducibility’ Walter Benjamin writes: “Photography freed the hand of the most important artistic functions, which henceforth devolved only upon the eye looking into a lens.” The liberation of the hand in painting by photography means the liberation of the painter from working from nature; instead nature is replaced by photographs, which serve as flat documents from which paintings can be created from a distance. As the philosopher Martin Heidegger noted, the world is conquered as (photographic) picture. It is this photographic picture that is replicated – “over and over and over again”, as in the title of Mullins’ painting of a Morning Glory flower – as ultra-thin barrier against the messiness of time and death.But every flat picture produces the very messiness of time and death for which the picture serves as an obstacle. In Mullins’ paintings time and death make their appearance through the motif of vanitas, which formed the basis of seventeenth century Dutch still life paintings of flowers – amongst other overlooked trivial objects, small wares, or trifles (rhopography). In Dutch still life painting rhopography challenges the grand schemes and historical narratives of megalography, shown to be vanity because of eternal fleetingness. While immersed in the materiality of the everyday, Dutch still life painting registers the everydayness of the everyday as a play of appearances, illusion, and deception. The paintings undermine their own power and ambition to recreate/ grasp/ freeze/ reflect the world, at the very moment that the world appears to be within reach. The paintings lament: life is brief and flimsy, because it is only a picture.Perhaps painted while remembering flat reproductions of Dutch still paintings, Mullins’ paintings or “cool memories” recall Gerhard Richter’s photorealistic paintings created from photographic documents that disrupt painting, but which turn around and disrupt photography. The photograph (as still life) reduces the painting of it to a floating lament for the Real. At the same time, the painting of a photograph bestows it with the aura of the once only. Absence and presence, proximity and distance, caveman (manual reproduction) and spaceman (technological reproduction) collapses. Place/space can be experienced, without necessarily being there. Like Richard Prince’s huge mirage-paintings of the simulacrum of Hollywood, Mullins’ flat-screen images of images increase our ambivalent nostalgia for death’s burn.

{H}