The retrospective ‘Umaf’ evuka, nje ngenyanga/Dying and rising, as the moon does’, opened at Constitution Hill in Johannesburg on South African Heritage Day – on 24 September 2022, curated by Azu Nwagbogu, Pippa Hetherington and Cathy Stanley. The exhibition showcases an oeuvre of large-scale tapestries by the Keiskamma Art Project, an artists’ collective founded in 2000 in Hamburg, Eastern Cape, by artist and medical doctor Carol Hofmeyr.

TOP: Women’s Charter Tapestries, 2016. 12 circular felt, applique and embroidery. Diameter: average 0.65m. BOTTOM: Creation altarpiece, 2007. Mixed media including felt, embroidery, photographs, beadwork, wirework and appliqué. Closed: 3.8 x 2.6m, Open: 3.8 x 4.6m Courtesy of Anthea Pokroy/Keiskamma Trust

The rural village, named after the eponymous seaport city in Germany, is steeped in colonial history. German soldiers who had been enlisted by the British to fight in the Crimean War in the nineteenth century, were instead re-routed to the Eastern Cape to create a settlement that would serve as a buffer between the Xhosa peoples and the British occupying forces. While little is left of the German settlers’ legacy, its contemporary gestalt shows a conjuncture of colonial and Apartheid spatial planning, cultural influence and forced disparity and an age-old, richly symbolic Xhosa cultural landscape.

The artists of the Keiskamma Art Project, predominantly women, use the art of fine stitching to depict local and global issues that affect their lives in a profound and material way. Their – often monumental – works require a dynamic, performative engagement on the part of the viewer. They demand space with their cinematic scale, but their extraordinary detail also draws one closer to a visceral interaction with an unfolding, ‘living’ tapestry: like a membrane inscribed with intimate stories.

Keiskamma Guernica, 2010. Mixed media incl appliqué, felt, embroidery, rusted wire, metal tags, beaded Aids ribbons, used blankets and old clothes, 3.5 x 7.8m. Courtesy of Anthea Pokroy/Keiskamma Trust

One of the seminal pieces, the Keiskamma Guernica (2010), is a rendition of Pablo Picasso’s 1937 oil painting, Guernica. While Picasso’s artwork depicts the cruelties of the Nazi bombing of the Basque town of Guernica in the north of Spain, it has over time transcended its context to become a metaphor for that unspeakable pain, whether inflicted by war or in the case of the Keiskamma Guernica, by the raging HIV/AIDS pandemic in South Africa that took so many lives. The piece is a form of reckoning, foregrounding complex socio-political and cultural issues around illnesses that still resonate, especially today, in a post-Covid world. The pandemic we all can relate to – from personal experience to the dramatic effects the world is still dealing with, the Covid Resilience Tapestry (2022) bears witness to loss, stillstand and isolation but also celebrates the power of nature and the re-awakening of care, a more gentle togetherness and ultimately – resilience.

Covid Resilience Tapestry, 2022. Fabric, embroidery, appliqué, 2.5 x 7.5m. Courtesy of Anthea Pokroy/Keiskamma Trust

Rose Altarpiece, 2005. Mixed media including fabric, appliqué, wirework, beading, embroidery, photographs and paper roses, 2 x 1.15m. Courtesy of Anthea Pokroy/Keiskamma Trust

The series of altarpieces – the Rose (2005), Keiskamma (2005) and Creation Altarpiece (2007) – are stand-out works in the exhibition. While their scale and level of detail recall many other works, they create a moment of surprise and animation that makes them distinctive. These pieces have often been compared to traditional European religious altarpieces and certainly do incorporate recognisable Christian symbolism. However their rather circular, rhizomatic narration depicts an attentiveness to the sacredness of the earth and the feminine divine: a spiritual consciousness rooted in connectedness. This is amplified by the spiritual significance of the Keiskamma River estuary alongside which Hamburg was built, seen as home to the spirits of the Xhosa ancestors, as Keiskamma artist Nozeti Makubalo has explained.

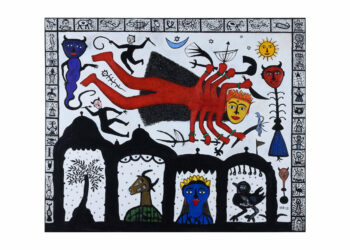

Keiskamma Tapestry, 2004. Embroidery on hessian with linoprints and beadwork, 0.7 x 120m. Courtesy of Anthea Pokroy/Keiskamma Trust

Many other South African artists also explore the country’s multifold history through creative interventions and art-making, creating works that seek to restore the understanding of indigenous belief systems and reclaim cultural meaning and identity. Artists like Athi-Patra Ruga, Thania Petersen, Billie Zangewa and Igshaan Adams have often centred materiality in their work; using fabric and tapestry as carriers of their creative investigations into historical representation and identity politics, topics we see presented throughout the exhibition.

While fine art and craft have always been close companions, their difference in terms of assigned value (monetary, archival and artistic) has often been restrictive, setting them apart. The Keiskamma artworks have often been simplified as ‘mere’ craftwork, and the frameworks in which they are typically shown and discussed underline their subtly pejorative categorisation. While one must recognise the crucial aid of the Keiskamma Arts Trust in fostering skills that offer women a livelihood and boost the local arts industry, the skillset of the Keiskamma artists expresses a unique visual language and aesthetic developed over two decades through collaborations and knowledge sharing. In contemporary discourse, these pieces deserve to be seen as important works of art, both locally and globally.

The question of the positioning of art within the larger art ecology is intricate, and with that, the ongoing quest to understand the process of art-making and studio practice. The Western notion of the artist as the sole creator and individual genius seems to persist even when factory-like production cycles have been common practice for centuries, demystifying the magic of birthing art as a sacred act. It is a fine line when considering what constitutes a piece of art. Is it the originality of the idea or its execution that distinguishes it from craft, design or consumable? And how would one define this originality? More often than not, these lines are blurred.

Whatever the ‘appropriate’ path of artwork production, art-making is an inherently collaborative act – credited through the collective practice or not. We see a re-emerging of the collective as a multitude of voices, skills and ideas presented through joint works. The impetus of collective work today seems more practical than ideological, more democratic than figure-headed, compared to its last peak in the West and the subsequent surge of -isms presented mainly by white men. The Indonesian ruangrupa collective curated this year’s documenta15 in Kassel emphasising artists’ collectives in their selection and sparked debates on contemporary art making and art presenting within an inclusive, diverse and democratic idiom. The Keiskamma artists have practised this collaborative art-making from the beginning: creating artworks in a collective studio practice that invites a shared process of labour, memory and healing.

In the end, the distinction between fine art and craft exposes the limitations of institutional language, its value-laden dichotomies prompting an obsession with what and how something can be articulated or categorised. The artworks in ‘Umaf’ evuka, nje ngenyanga / Dying and rising, as the moon does’ defy a simple translation into words. They need to be seen and experienced in situ for us to comprehend their depth, complexity and beauty.

The exhibition is on view until the 24th of March 2023. For more information, please visit the Keiskamma Art Project and Constitution Hill.

Nisha Merit is an independent curator based between Johannesburg and Berlin.