Fires burn all the time, everywhere, and yet, despite their frequency, some fires, particularly those involving libraries, resonate across time. Alexandria, Constantinople, Timbuktu and, more recently, Cape Town, all these cities have seen their great libraries go up in flames. Knowledge, or at least the paper that has ensured its transmission for centuries, is fissile material.

Installation view of ‘Eternal Circumstances’ at Everard Read. © Diana Vives

In the first expansive presentation of her narrative-infused sculptural work since graduating from the Michaelis School of Art at the University of Cape Town (UCT) in 2020, Diana Vives, currently a MFA candidate at the same art school, recently presented an impressive suite of six new sculptural works incorporating detritus from a library fire in her hometown.

Blue protects white from innocence

Blue drags black with it

Blue is darkness made visible

Blue protects white from innocence

Blue drags black with it

Blue is darkness made visible.

Derek Jarman

On a clear Sunday in April 2021, a desultory bush fire on the slopes of Cape Town’s Table Mountain, fanned by berg winds, grew into a conflagration that devastated parts of UCT. The historic Jagger Reading Room, built in the 1930s, was destroyed – and along with it some 70,000 printed documents from the African Studies collection. Fire and water are equal agents of destruction in library fires. Two days after the Jagger Library fire, a technical team discovered that its basements had been flooded with water during the rescue operations. A triage tent was established. Within a week, a cold storage container was brought on-site to stabilise materials. Salvaged materials were prepared for later freeze-drying.

“If to ‘save’ is to rescue from destruction, ‘salvage’ is about retrieving that which is no longer archival or even tangible – not just to preserve the emotional memory of the event, but to make something from its sacrifice,” wrote Vives in a note accompanying her exhibition ‘Eternal Circumstances’ at Everard Read, Cape Town. During a walkabout of the exhibition, part of the Everard Read’s on-going Cubicle series of artist presentations, Vives detailed her experiences of volunteering during the library rescue and clearance. Two of the works in ‘Eternal Circumstances’ feature fire-scorched documents from the Jagger Library fire discovered with artist Sophie Cope, winner of the 2020 Michaelis Prize.

Air rights, 2022. Bookbinder’s mull cloth, paper, wood and brass, 89 x 84 x 40cm. © Diana Vives

Air Rights (2022), a suspended box kite based on a design from the 1890s by the aeronautical pioneer Lawrence Hargrave, is noteworthy for its use of bookbinder’s mull and hand-drawn star charts jettisoned as fire rubble. The charts depict Phoenix, a minor grouping of visible stars in the southern sky. Together with Grus, Pavo and Tucana, Phoenix forms part of the “southern birds”, star arrangements exclusively visible in the Southern Hemisphere. A potent raw material, the burnt charts can be induced to yield further meaning (notably involving stellar growth and decline), but as a physical object nattily suspended with a plumb line, the kite was a joyful and fascinating thing to behold. This pull between surface and depth is a hallmark of Vives’s work.

Eternal Circumstances, 2022. Ed. 1/3, Cyanotypes on arches paper, wood, brass & bookbinder’s mull, 160 x 233 x 10cm. © Diana Vives

Eternal Circumstances, for which her exhibition was named, similarly features star charts, albeit for the “water constellations”. Vives produced 11 hand-stitched books featuring 22 cyanotypes (photographic blueprints). The blue pages depict the star charts overlaid onto a poem by Stéphane Mallarmé. “Poem” is far too coy a word for Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard (A Throw of the Dice will Never Abolish Chance). Vives, who derived the title of her exhibition from Mallarmé’s posthumously published verse of 1897, describes this visual poem as a “typographic construction”. Mallarmé’s directives for its publication are perhaps more instructive: “The poem is spread over 20 pages, in various typefaces, amidst liberal amounts of blank space. Each pair of consecutive facing pages is to be read as a single panel; the text flows back and forth across the two pages, along irregular lines.”

First published in book form in 1914, the smallness of Vives’s recent book edition matches that of the original, which was limited to 60 copies. Each presented splayed open on 11 irregularly positioned ledges, Vives’s book installation intrigued, not because of its literariness, which is in any case sublimated, but rather for the chromatic richness of the cyan-blue prints. Blue has much occupied young Cape Town artists, among them Shakil Solanki and Mia Thom, both of whom have appreciatively quoted Derek Jarman in recent projects. “Blue protects white from innocence,” wrote Jarman in a poem. “Blue drags black with it / Blue is darkness made visible.” Arguably, blue also makes the darkness of a charred celestial world more visible in Vives’s impressive installation.

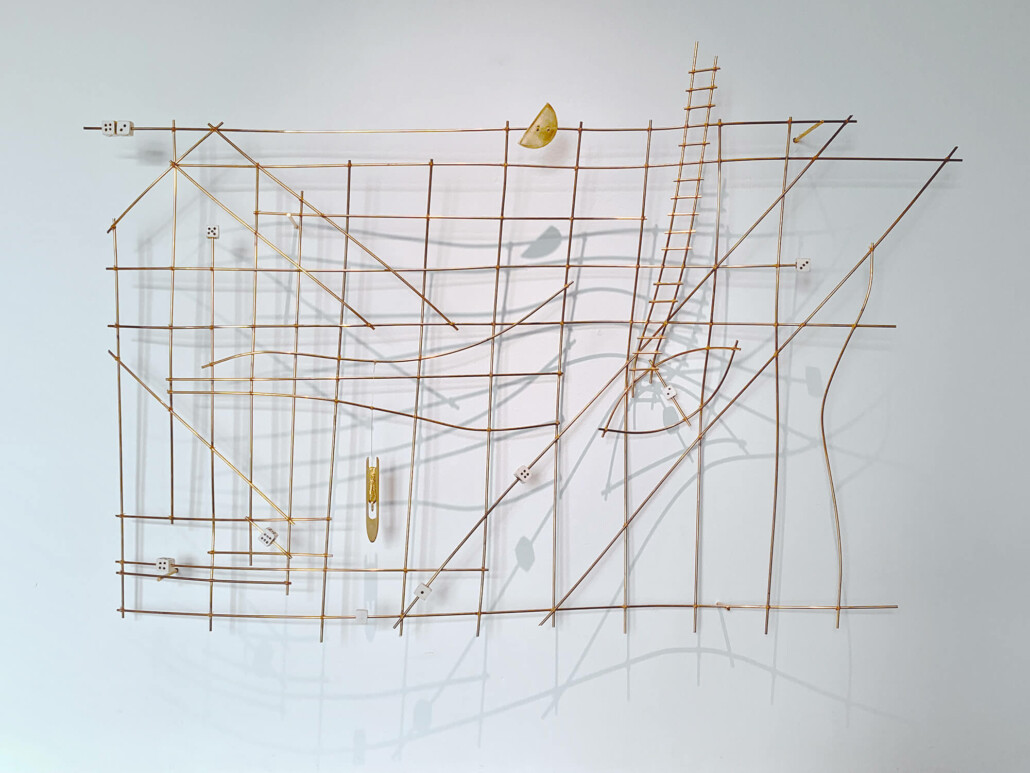

If The Seas Catch Fire, 2022. Brass rods, brass wire and porcelain dice, 70 x 100 x 150cm. © Diana Vives

In a note accompanying her exhibition, Vives writes that the exactitude of digital observation systems has somewhat diminished the value of hand-drawn star maps, at least for modern astronomers. Stars, though, remain integral to navigating the oceans, a multitudinous blue of many tonalities. Vives however ignores the stars completely in her most enigmatic work to date: the wall-hung sculpture If the Seas Catch Fire. This rectangular work is composed of a grid of brass rods and wire with additional appendages of porcelain dice, a semi-circular disc and metal replica of a shuttle tool for weaving. The work’s form references so-called “stick charts”. Made from coconut and palm strips with cowrie shells affixed onto the grid, this non-western technology was used by Micronesian seafarers from the Marshall Islands as navigation devises and abstractly visualised knowledge of currents, wave and wind patterns. If the Seas Catch Fire draws on an enigmatic form to present an autobiographical map, its information, such that it can be read, inscrutable.

Vives, who was born in Brazil, grew up in South Africa and Switzerland, and has lived in France, Germany, United Kingdom and United States, is an unconventional bright young thing on the scene. Roundabout her fiftieth year, having attended private art classes and navigated a divorce, she decided to pursue art professionally. She enrolled at UCT, made friends, hustled, collected things, made work. Her ambitious sculptural practice, which encompasses an astonishing diversity of new and found materials, draws strongly on her nomadic biography and deep affinity for books, those things libraries house.

The Sky Beneath, 2022. Brass and wood, 50 x 60 x 180cm. © Diana Vives

“Perhaps it is due to this peripatetic life that I relate to the passante, the female equivalent of Charles Baudelaire’s flaneur: the observer who wanders through the spaces of modern life with an acquisitive eye, an archetypal modernist explorer,” wrote Vives in a catalogue for her 2020 graduate exhibition, Nobody, Nowhere. A confident follow up to this opening salvo, ‘Eternal Circumstances’ was consistent with her aim – first verbalised and quoted from Walter Benjamin – to derive “the eternal from the transitory” and to see the “poetic in the historic”, be it stone, metal or a charred book of star drawings retrieved from a vanquished library on the slope of an ancient mountain known to replenish its ecosystem by fire.

Sean O’Toole is a writer and curator living in Cape Town, South Africa.