A Reflection by Francois Knoetze and Oulimata Gueye

A “core dump” is the recorded state of the working memory of a computer at a specific moment in time. If a crash occurs, the computer is able to recall this ‘imprint’ of its previous state as a means to debug and recover. This oddly poetic ‘memory’ of a computer forms the basis of Francois Knoetze’s Core Dump (2018-2019). The four-part sculptural and video series, filmed in Dakar, Kinshasa, Shenzhen and New York, extends the metaphor of a crash to the impending breakdown and unsustainability of the global capitalist techno-scientific system which is characterised by a glut of excess and a fascination with hypermodernity masquerading as progress.

The following conversation took place in Paris in October 2019 between critic and curator Oulimata Gueye and artist Francois Knoetze, shortly before the opening of Cosmopolis II, which features Core Dump, at the Centre Pompidou.

Francois Knoetze, Core Dump – Dakar, 2018. Production still by Mouhamadou Diene. Featuring Bamba Diangne. All images courtesy of the artist.

Francois Knoetze, Core Dump – Dakar, 2018. Production still by Mouhamadou Diene. Featuring Bamba Diangne. All images courtesy of the artist.

Oulimata Gueye: Our starting point in the Digital Imaginaries project was: Africa is radically changing, and digitisation features prominently in contemporary African imaginaries and realities. The mobile phone boom and the development of mobile-enabled banking services demonstrate that African-specific digital practices are very lively and starting to shape globalised digital technologies. The diverse digital scenes that emerged in the few well-connected African hubs provide new perspectives, metropolitan pride, and a sense of global participation. One reading of these developments is that Africa is arriving in the global digital sphere. This reading relies on one of the founding digital imaginaries of the Internet as a seamless space that is universalising modes of access and participation globally. Digital inequality has mainly been conceived as a divide between those who can and those who cannot easily access the Internet. Now that access is increasing, it is evident that access alone does not level the playing field.

In Dakar, as part of the Non-Aligned Utopias chapter, you were invited to research the issues and critical positions that accompany the development of digital culture on the continent. It seemed appropriate to reactivate a utopian contemporary imagining of the Non-Aligned Movement’s initial research into this subject.

Francois Knoetze: When I started my research, I came across a video of a speech by Leopold Sédar Senghor at the Conference of Developing Countries on Raw Materials, which took place in Dakar in 1975. This conference was organised in an effort to guard against the plundering of raw materials and the dumping of hazardous waste – a key feature of the global capitalist system. I wanted to explore questions surrounding Digital Colonialism, and how it was possible for the raw materials used in the digital technology industry to be mined in the DR Congo, transported around the world, and end back up on the West coast of Africa as E-waste.

Core Dump – Kinshasa, 2018. Photographer: Jean Babtiste Joire.

Core Dump – Kinshasa, 2018. Photographer: Jean Babtiste Joire.

I viewed these pieces of electronic waste as artefacts – radioactive fossils – which speak to the power relations forged in the Trans-Atlantic during the nineteenth century and the dependence industrialisation had on slavery. This established long-enduring binaries between race and technology, nature and civilisation.

I set out to look at how these practices are still deeply ingrained in the current supply chain and popular media representations of the technoscape, foregrounding strategies for artistic and political resistance which include the Non-Aligned and Negritude Movements, and the glimmering imagination spaces of early African cinema. The films draw from audio-visual archives, the pan-African, Marxist utopias of early African cinema, specifically the films of Ousmane Sembene, and a range of writers and thinkers – from Donna Haraway and Louis Chude-Sokei to Gayatri Spivak and Aimé Césaire.

With the Non-Aligned Utopias project, we were exploring issues such as: Is it possible to design and develop digital technologies and practices not aligned with hegemonic and neocolonialist models? Are digital technologies solely products of Western culture? Are there laboratories for alternative practices? Are other futures possible or desirable? Can we still think in terms of utopias if we consider, like sociologist Joseph Tonda, that we are ruled by the tyranny of screens?

Tonda’s work, which informed your Kinshasa film, illuminates the strange times we are living in, suggesting that we have entered an era of postcolonial imperialism in which the African continent is subject to the same liberal techno-capitalist economic regime as the rest of the world.

While in Dakar, I was lucky enough to be able to interview Joseph Tonda. He recounted a Congolese urban legend which formed the basis of the chapter I shot in the DRC – an Afro-dystopian Sci-Fi horror that attempts to represent Tonda’s theories surrounding the Congolese imagination within Colonialism. Through situating popular myths in the contemporary digitised imagination, this chapter speaks to the conceptual connections between the West’s notions of tech utopias and the strategic underdevelopment of the former colonies it mines and dumps on to create these shimmering oasis.

Core Dump – Dakar, 2018. Production still by Anton Scholtz. Featuring Bamba Diangne.

Core Dump – Dakar, 2018. Production still by Anton Scholtz. Featuring Bamba Diangne.

My research and practice in this project seeks to interrogate how knowledge monopolies like Google, Apple, Microsoft, and Facebook have falsely represented notions of ‘progress’ and ‘technology’ as products of the West. While the electronics hardware supply chain taps into old colonial trade arrangements, the software of these corporations seek to colonise emerging markets in Africa, in the process sweeping aside indigenous knowledge systems by imposing a centralised and homogenised cloud economy.

Mami Wata is a mythical water goddess who appeared after the people from the Ghanaian coast encountered the European vessels accosting Africa in the late fifteenth century. Being hybrid and mystical, she provides wealth and power to the people she seduces in return for their total devotion. Goddess of change, she augurs economic, social, cultural and political change. Tonda describes Mami Wata as a postmodern and postcolonial figure – woman, half-white, half-black, half-human, half-animal (so transnature and sometimes transgender), provider of material wealth, prestige and power.

In the Shenzhen chapter, Mami Wata is transplanted into the context of the ‘world’s gadget factory’. In 2012, images and videos of Mami Wata began to rapidly circulate online across the DRC, sparking rumours that Chinese labourers had captured her while they were installing underwater fibre optic cables in the Congo River. In this chapter, I use Mami Wata’s capture as a point of departure for the narrative, unfolding ideas surrounding the transmutation of myth in the Age of Internet, and the ability of digital platforms to reveal the depth and complication of contemporary Sino-African relations.

Core Dump – Shenzhen, 2018. Photographer: Zidan. Courtesy of the Execution Team of Cosmopolis #1.5.

Core Dump – Shenzhen, 2018. Photographer: Zidan. Courtesy of the Execution Team of Cosmopolis #1.5.

The Sound of Culture: Diaspora and Black Technopoetics by Louis Chude-Sokei was the starting point for the New York chapter. The author notes the importance of recognising the existence of a connection between black slavery and the machine, referring to the way in which slaves were reduced to human machines for white exploitation, and to white anxiety about a slave revolt.

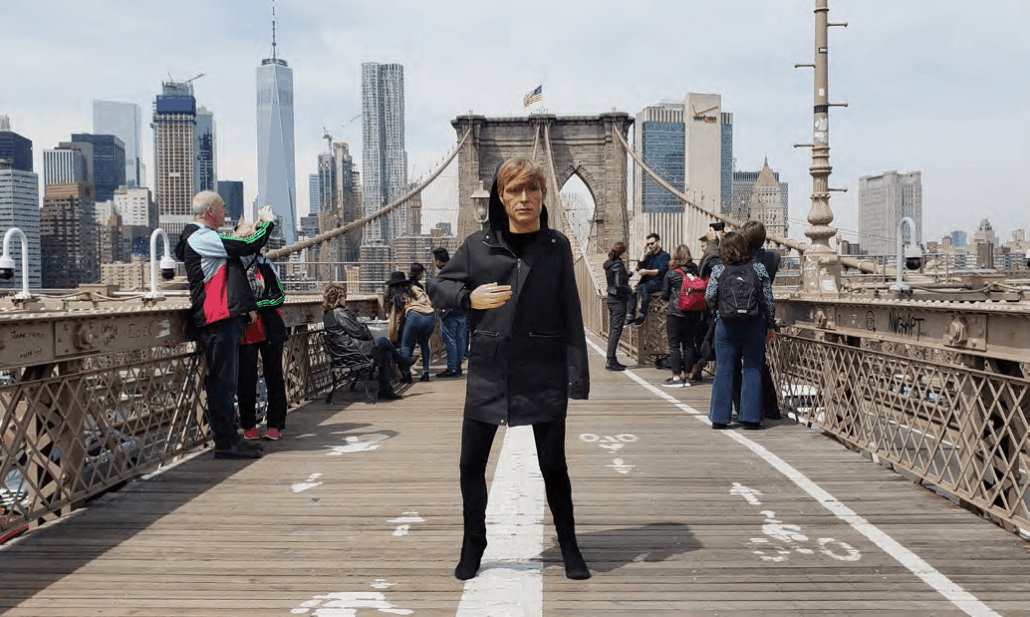

Yes, Chude-Sokei’s writing on this subject, as well as Céline Keller’s expansion of Sylvia Wynter’s work on humans, machines and animals, were the primary source of inspiration for this chapter. Plot-wise, in New York I took the robot ‘Big Dog’, developed by Boston Dynamics, as a starting point, imagining this robot escaping from the lab and finding its way to the city. This chapter contests the idea of New York as a site of freedom and progress, depicting it instead as a maze of difficult-to-navigate codified signs and systems. In this film, we follow the journey(s) of the robotic character as it is severed in two by the doors of a train, setting the scene for a split-screen journey through the city, ending with its eventual dumping as part of a shipment of electronic waste back in Dakar.

In these films, I created narrative portraits of the uncertainty in the nervous system of a global digital machine on the brink of collapse – an imprint of our Digital Earth in this precarious moment. The stories which unfold in each of the cities compare critical contexts and histories to suggest that, although technology is rapidly evolving, patterns of exploitation are deeply ingrained in the way it has and continues to be produced, consumed and represented, and that the crucial technologies involved in moving towards a more equitable world are less physical than they are social. The series tries to uncover ways in which the materiality and immateriality of digital reality have played out to devastating effect across the continent, highlighting the need for embedding empathy into the circuitry of human relations that constitute the Digital Earth.

Core Dump – New York, 2019. Featuring Amy Louise Wilson.

Core Dump – New York, 2019. Featuring Amy Louise Wilson.

Produced in cooperation with Kër Thiossane (Dakar), Wits Art Museum (Johannesburg), KINACT (Kinshasa), 33 Space (Shenzhen) and ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe for the project Digital Imaginaries. The project was funded by the TURN Fund of the German Federal Cultural Foundation. This project was supported by an ANT Mobility Grant from Pro-Helvetia Johannesburg, financed by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation. This project forms part of the Digital Earth Fellowship, initiated by Hivos, SIDA, and The British Council.

Oulimata Gueye is critic and curator for the non-for-profit platform Xam Xam. She studies the impact of digital technology on urban popular culture in Africa. Her fields of investigation include: Africa sf on digital culture, science and the potential of fiction to develop critical analysis and alternative positions; Afrocyberféminismes that explore digital technologies and the associated stakes in contemporary Africa and its diasporas, namely by investigating the place of gender and race. She was co-curator of Digital Imaginaries, a joint project of Ker Thiossane, Wits Art Museum, Fak’ugesi, and ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe.