Forging an archive in the audible world

Ali Tnani, Even the Sun has Rumors, 2017. Multimedia installation, variable dimensions, 18 mn (part 1), 17mn (part 2), loop. Courtesy of the artist.

Ali Tnani, Even the Sun has Rumors, 2017. Multimedia installation, variable dimensions, 18 mn (part 1), 17mn (part 2), loop. Courtesy of the artist.

ART AFRICA spoke to Bonaventure Ndikung regarding his transdisciplinary project planned for the collective show he will be guest curating at the Dakar Biennale, open from May 3rd to June 2nd. The Cameroonian biotechnologist and independent curator’s show will explore the life of Egyptian electronic musician and ethnomusicologist Halim El-Dabh, raising pertinent questions relating to the disruption and construction of archival knowledge.

ART AFRICA: Each guest curator at Dak’Art will be curating a collective show with 3-5 selected artists. Could you discuss the artists you have chosen for the biennale?

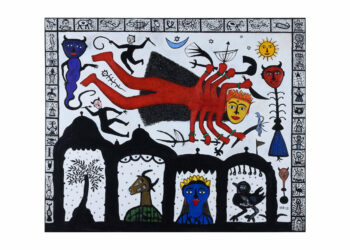

Bonaventure Ndikung: The show I’m doing is with 14 artists and not 3. It will include Halim El-Dabh, Younes Baba Ali, Leo Asemota, Satch Hoyt, Tegene Kunbi, Memory Biwa, Robert Machiri, Ibrahim Mahama, Nyakallo Maleke, Elsa Mbala, Yara Mekawei, Emeka Ogboh, Sunette Viljoen, Ima-Abasi Okon, and Junior Boakye-Yiadom. The project is called “Canine Wisdom for the Barking Dog”, and it continues, the “The Dog Done Gone Dead”. It’s a tribute to the composer Halim El Dabh, who was from Egypt. He was born in 1921 and died in 2017. He revolutionized electronic music in the 20th century – but of course he has been completely written out of the canon. The fact is that his compositions were instrumental to many other artists. He collaborated with a lot of American and European artists and he himself went to the US in the 50s and stayed there until he died. There are two big phases in his practice – the early phase is the composition based on the technique of what was later called musique concrète. His composition The Expression of Zaar in 1944 preceded what the French so-called founders of musique concrète did in 1948; before musique concrète was founded, Halim El-Dabh was already using these techniques. He spent his life composing, for theatre, for dance, for famous dancers like Martha Graham and many others – that’s one part of his practice. Another part is his travels across the African continent working as an ethnomusicologist. What I’m interested in is revisiting his work, his practice, but specifically when he went to visit Dakar in 1957. He did a couple of recordings there in the market square and I’m interested in making the link between those recordings then and now. The artists I’ve invited, some of them knew Halim El-Dabh and some of them didn’t, so the question is: how do we write history? How do we take upon ourselves the responsibility of carrying a legacy? The challenge for the artists was to indulge, to dive into Halim El-Dabh’s life, compositions, and practices in art. The results have been very varied – some have worked more with sound, some have worked with visuals. Halim El-Dabh was also a painter, which not many people know about. His paintings were more like scores; he would paint on canvas to make a notation system to make music. It becomes very interesting because he was synaesthetic – thus he wrote his music with colours and shapes.

The 2018 theme for Dak’Art is ‘The Red Hour’. How do you understand this theme and how do you seek to interpret this theme in your curatorial work?

I don’t seek to do that. It happens.

Frances Goodman, Roiling Red, 2018. Wood, fiberglass, polyurethane foam, silicone glue, acrylic false nails, 2540 x 1530 x 280mm. Courtesy of the artist.

Frances Goodman, Roiling Red, 2018. Wood, fiberglass, polyurethane foam, silicone glue, acrylic false nails, 2540 x 1530 x 280mm. Courtesy of the artist.

You founded Savvy Contemporary in Berlin with the intention of creating a space “whereby ‘Western art’ and ‘non-Western art’ can communicate and exchange on a par with one another”, critiquing in part how the West views non-Western art as an exotic cliché. In your approach to a biennale hosted in Senegal, in the othered Africa, how does this translate?

At the core of Savvy is the question of the moment of encounter and what we do with, it is about finding ways of re-narrating the story. I’m from Cameroon and there is a way of speaking and a way of doing things that we would call a philosophy. I’m interested in how we bring our own philosophies to the space of cultural discourse. It translates to Dakar in the concept of Halim El-Dabh and his philosophy of music. When Halim El-Dabh talks about the emergence and decay of music in his composition process, how do we apply that? It goes beyond anything that we’ve heard of in the West. I’m not the first person to talk about this – in 1977 Jacques Attali wrote a book called ‘The Political Economy of Music’. He wrote that Western knowledge in the 20th century tried to look at world but Western knowledge failed because it tried to look at the world. Jacques Attali would say that the world is not legible – it is audible. I am interested in listening to the world; I wish to emphasize the importance of sonority, the character of sound, the kind of knowledge embedded in sound. Of course, I use these subjective terms of the West and the non-West to deconstruct them and I’m interested in finding ways of doing that through the mutual interest in the sonic practice I share with the people I have invited.

You’ve expressed your interest in Heinrich Heine’s idea of aesthetic revolution. How does this inform your curatorial process?

The aesthetic revolution has to do with a reconfiguration of the way the world is perceived, which is to say the way we are trained to see the world. The aesthetic revolution comes in these practices of training and untraining the beholder and the way we listen, to untrain the way we navigate spaces. It’s a deeply phenomenological thing: the way we experience spaces. When we do that we need to propose new things and I’m interested in the notion of the deeper archive, the immaterial, which is to say from where do we tap knowledge? From where is knowledge sourced? I want to find knowledge in witchcraft, that thing called madness, in performativity, in dance. Those things we were told not to respect, because by respecting them we honour false gods, because by living them we are uncivilised, barbaric. It’s about knowledge of the barbarian, about finding knowledge in the corners of the room, those spaces where people don’t speak loud, but whisper. It’s about finding knowledge in the non-obvious, finding knowledge under the surface. It’s also efforts of not being enlightened, swimming against the stream of enlightenment, staying in the dark, understanding darkness as a space of knowledge, power. It’s about not being forced into a space of concepts of light as a metaphor, as a function.

Amita Makan, My Feet (detail), 2012. Hand embroidered with silk, viscose thread, vintage sari on silk organza. (The work is encased in perspex to be viewed recto and verso), 125 x 82 x 3.3cm. Courtesy of the artist.

Amita Makan, My Feet (detail), 2012. Hand embroidered with silk, viscose thread, vintage sari on silk organza. (The work is encased in perspex to be viewed recto and verso), 125 x 82 x 3.3cm. Courtesy of the artist.

Zahra Abba Omar is an intern on ART AFRICA‘s editorial team.