Off Biennale Cairo and AtWork workshop:

An alternative way to look at art and education

Internationally acclaimed curator Simon Njami spoke to Elena Korzhenevich about the first edition of the Off Biennale Cairo, entitled ‘Something Else,’ and the AtWork workshop, which took place in November 2015. This interview provides insight into alternative ways in which contemporary art is practiced, curated and perceived in Egypt and its surrounding areas.

Darb 1718 artistic centre in Cairo

In November 2015 in Cairo, Egypt, something else happened. Something that provided an alternative to the way contemporary art is practiced, curated and perceived in this part of the world. Something that favoured connections between different artistic and cultural communities and promoted innovation and social change through culture. With these aims in mind, the prominent Egyptian artist Moataz Nasr and the internationally acclaimed curator Simon Njami were prompted to create and bring into existence the first edition of the Off Biennale Cairo, entitled ‘Something Else.’

Simon Njami invited eight international curators to select local and international artists for the Off Biennale. With the addition of his own choices the selection arrived at the final number of one hundred and one artists who would participate in a month-long event, which took over the city with exhibitions, performances, workshops, film screenings, talks and panels. The artists and audiences had a chance to establish a conversation on contemporary art production in Egypt and Northern Africa, to confront the artistic practices of Egyptian artists and to reflect on what it means to be a contemporary artist today in Egypt and beyond.

But ‘Something Else’ was not just about art and established artists. It was also about education and involving young creative talents in the conversation on contemporary art production and its role in society. The AtWork workshop which took place at the heart of the Off Biennale at Darb 1718 Contemporary Art & Culture Center, had this aim as its core focus. AtWork is an educational format, conceived by the Italian non-profit foundation lettera27 and Simon Njami, that uses the creative process to stimulate critical thinking and debate among the participants. At the end of the workshop each student produced a personalised Moleskine notebook which consolidated the process of self-reflection triggered by the workshop. AtWork Cairo was the fourth chapter of the format that lettera27 has implemented on the African continent since 2012, with previous editions held in Dakar, Abidjan and Kampala.

In Cairo, the three-day AtWork workshop was led by Simon Njami and facilitated by the American University of Cairo’s art assistant Professor Heba Amin. The workshop involved sixteen art students and drew its theme from the title of the Off Biennale: ‘Something Else.’ It was an opportunity for

the students to discuss alternative perspectives on their art practice; a way to question their certainties, step out of their comfort zones and practice critical thinking in such a complex context as Cairo. The workshop – also attended by some of the Off Biennale’s protagonists, including Ayana V Jackson – allowed the students, as well as local and international artists, to exchange and share ideas on contemporary art production.

Youssef Limoud, one of the artists participating in the Off Biennale, described his experience as such: “Simon has really touched on the main problem of the Egyptian art scene, especially in relation to the young people here who practice contemporary art. They don’t really know what ‘contemporary’ means. I always think that the main problem with the art scene in Egypt is this lack of education. The only way to help new generations to use their minds, to put them on another level, is to have more of these workshops.”

Limoud’s perspective is echoed by the art Professor Heba Amin, who said: “We grew up in an educational system where we were not allowed to think for ourselves, we weren’t allowed to question, we weren’t allowed to have an opinion. When we talk about the environment that is very politicised, that is censored, that is surveyed, the only place where criticality is occurring is in the art world. So it’s really important to involve workshops like AtWork within the educational and institutional setting because this allows students to explore intellectuality, curiosity and criticality in ways they might not in the classroom.”

The resulting art notebooks will be exhibited in March 2016 at Darb 1718 in a show co-curated by the students. After the show the students’ artworks become part of lettera27’s artist notebooks collection alongside prominent contemporary artists like Pascale Marthine Tayou and Nicholas Hlobo.

The Off Biennale is over now, but the imprint it has left on the local art scene, on the students and audiences will have a long-term effect. The event was only possible because of the energy of the individuals who believed it was necessary to start thinking about art differently, to bring some new energy, to break the pre-established schemes and to propose something else. As Moataz Nasr put it, “it was all for the sake of the people and their good.”

Elena Korzhenevich interviews Simon Njami

During the Off Biennale lettera27’s Elena Korzhenevich spoke with Simon Njami about ‘Something Else’ and the AtWork workshop.

Simon Njami during an AtWork workshop in Cairo. Photo: Luca Dimoon.

Elena Korzhenevich: So, why ‘Something Else’?

Simon Njami: I’ve been coming to Egypt for quite some time, and Moataz Nasr and I have always complained about the contemporary art situation, the conservatism and the lack of curiosity and knowledge. We wanted to do something about that. The first step was the opening of the art centre Darb 1718, but then we needed to make an event. We wanted to do something that would open at the same time as the official Cairo Biennale, but to do ‘something else.’ The Cairo Biennale is institutional and it works according to the ancient rules inherited from the Venice Biennale (national pavilions and such). Therefore, the spirit of the biennale is kind of old, from the way they select the curators to the way it’s curated – and it’s very governmental. Our aim was not to delete the biennale, but to offer an alternative kind of event, hence the title, ‘Something Else.’ Then the biennale was postponed, but we decided we would do ‘Something Else’ anyway. The philosophy behind it was to bring a bunch of people here to show the diversity of what is called ‘contemporary art,’ to attract foreigners to interact with Egyptian artists, to initiate a dialogue and to haveakindoflearning-by-livingexperience through a constructive confrontation with other practices, other philosophies and other approaches. The other thing that was important, as I say quite often, is that art is not what is important about art. What is important is the people. ‘Something Else’ took place because Moataz and I are old friends and we invited other friends to a welcome table where things would happen. I’ve always been fascinated by the Greek notion of a symposium, so we made a symposium.

Can you talk about the interaction with ‘Something Else’ from the people of Cairo? How did it extend to the larger audiences beyond just the artists participating in the Off Biennale?

When this kind of event is done, it has an educational purpose directed to the local art scene and to the larger audience of citizens of Cairo. It’s always tricky to initiate a contemporary art event because you have to get people to enter the spaces and people don’t necessarily tend to go to art centres or museums, so we brought the contemporary art to them. We had, for instance, a performance in this shop in front of the movie theatre. It was interesting to see how the audience reacted when Romina De Novellis was performing. I had people coming up to me to ask what was going on and why she was cleaning the floor. This kind of interaction is important in the educational sense, because the people who were just passing by the shop were confronted with things that they don’t see every day.

Romina De Novellis, NA CL O, performance. Photo: Mauro Bordin © DE NOVELLIS / BORDIN 2015.

In general, what role do you think art can play in the social transformation of Egypt and Northern Africa? And specifically, where is the convergence of art and education?

I’ve always been passionate about education. Art is not what is important to me. What is important to me is transmitting things, exchanging things, sharing things. Art is the perfect tool for this, because art is something everyone can understand. It’s a kind of Trojan Horse, a kind of sniper – it’s always undercover and can convey messages in a way that a political slogan couldn’t. It can touch people in a manner that politics can’t, because it deals with senses, with the mind and with awareness. I think people who are confronted with art will be a bit freer to think about themselves, and someone who is free is someone who is willing to transform their society. The artist is nobody special, just one person among many others. As a citizen and one has to play a role as any other citizen does. So the fact that in certain countries like Egypt art is not taken seriously, allows the artists to convey messages that politics would not be able to read or decipher, but that could be read and understood by the public.

If you had to name other similar initiatives and biennales in Africa what would they be?

When I think of what we did in Cairo, I think of what is done in Africa and I mainly concentrate on those initiatives that come from private individuals. I think of doual’art, which was initiated by two private individuals (who are not artists) and who are making a triennale in Cameroon. I think of PICHA in Lumbumbashi (Congo), which was initiated by photographer Sammy Baloji. The goal of this biennale is the same as our own – to educate, to open up, to share. I think of the Lagos Photo Festival, the Addis Foto Fest in Ethiopia and the Luanda Triennale in Angola. All these initiatives are driven by the same force, but of course every context is different, so it’s always important to create things that are site-specific. There is no such thing as a recipe and that’s what the officials often don’t understand. In order for something to work it has to be grounded and anchored in the specific soil, if not it will not grow.

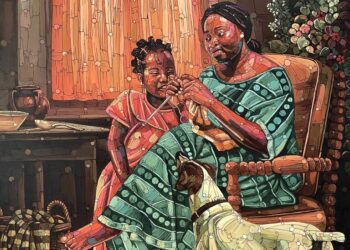

Youssef Limoud, Makam, 2015. Courtesy of the artist.

You decided to include the AtWork educational format in the programme of the Off Biennale Cairo. Why was this particularly important in the educational context of Cairo?

When we started AtWork it was based on reflecting on the education system. This applies to the African continent, but of course this applies to any continent and any country. The educational system is made out of homework and evaluations. You have to perform a certain job to get a certain paper. What AtWork brings is precisely the fact that there is no model: they have nothing to learn, they have to feel and then they have to decide for themselves. They are the ones grading themselves, we are not giving them any papers or certificates. AtWork allows them to reflect on themselves and to try different manners that might help them in academic courses, because they will learn how to play with different tools. In a traditional academic system you are given tools that would help you to pass the different exams. AtWork is providing them the toolbox, but then we just put a couple of tools in that box and then make sure they understand that this box will be operative only if they themselves carve their own tools and if they continue the job.

Why ‘Something Else’ as a theme for the AtWork workshop?

Since I named the event ‘Something Else,’ I thought it would be a very good theme for AtWork. I find the Egyptian society to be very conformist, very traditionalist. When I say traditionalist, I don’t necessarily refer to religion, just the people who do things the way things ‘should’ be done. So the kids are trapped in the same system of replicating what they are taught to replicate, not necessarily feeling it or understanding it. So, I thought ‘Something Else’ would be the perfect theme for this workshop, because all of a sudden the kids are asked to get out of their comfort zone, to get out of their boxes, out of their ideas for the duration of theworkshop. I think this kind of experience, even if it lasts a short amount of time, is somethingtheyshouldnotforget.Ittakesa lot of effort to realise that you are living in a cage, and to be conscious of your cage is the first step towards freedom.

AtWork workshop at Darb 1718 art center in Cairo. Photo: Luca Dimoon.

Is there anything specific to AtWork in Cairo?

There is always something specific when we do AtWork – it’s the context. Here kids are always talking about the revolution and there is a certain political situation in this country, which affects the way people move, the way people feel, the way people think and it affects the way I address the kids here, because I know what they are going through. I have an understanding of their contextual prison. So every AtWork is different according to its context and our job is to find the right manner to address the kids.

How do you measure the workshop’s success?

There is something tricky about these kinds of workshops because you don’t have a tool to evaluate what happened. I have forged a personal tool that I have used in all of my

workshops: there is a before and there is an after. I see the kids for the first time, we starttotalk.Then,whenwesaygoodbyeto each other, my way of evaluating is the way they say goodbye. The way they smile, the kind of jokes they make, the body language they have. That will give me an indication that something happened, that even within a very short period of time, something changed in them. That’s the only way I can evaluate it. Yesterday I was amazed by how doors can open. Here are kids who are very cautious, very shy and educated in a certain manner and, all of a sudden, they were giving me the deepest of their souls in front of the others, and I found that wonderful. I was so proud of them.

Elena Korzhenevich was born in Moscow, Russia. She holds a MS degree in Mass Communications and Journalism from San Jose State University, CA, USA. She has extensive professional experience in communications, having worked at major international advertising agencies in Italy and the US. In 2014, she joined lettera27, an Italian non-profit cultural organisation, where she is currently a Communications Director.

This interview was first published in the March 2016 issue of ART AFRICA, ‘Looking Further North.’